Introduction

The AKP's refusal to seek a consensus presidential candidate, its uncompromising effort to appoint "a religious [i.e. Islamist] president" from the AKP ranks, the secrecy surrounding who their candidate would be, and the last-minute announcement of Turkish Foreign Minister Abdullah Gul from the Islamist Milli Gorus movement as the candidate, have all pushed Turkey into a political crisis.

Millions of Turks participated in demonstrations against the AKP government, its Islamist agenda, the appointment of Islamists to key positions in public institutions, and especially against the attempt to nominate an Islamist presidential candidate – a nomination that would jeopardize Turkey's system of checks and balances, creating a situation where both the prime minister and the president belong to the Islamist camp.

Prime Minister Recep Tayyip Erdogan's political moves provoked a controversial memorandum from the Turkish military establishment, which is – traditionally and by the power accorded to it in the constitution – the guardian of the secular regime in Turkey.

On presidential election day, members of the opposition parties boycotted the election by not participating in the first round of the vote, and the necessary quorum of 367 MPs (two thirds of the 550-member parliament) was not reached. The matter ended up in the High Constitutional Court, which decided to annul the first round of the vote.

The mass demonstrations, the memorandum by the military and the High Court's decision forced the AKP to declare early parliamentary elections, to take place on July 22, 2007.

The Political Scene

Turkey's election system – which, during its five years in power, the AKP has refused to change – allows only parties receiving 10% of the vote nationwide to be represented in parliament. This threshold, unusually high for a democracy, keeps many smaller parties out of the legislature. It was this factor that brought the AKP to power in November 2002, when it received a two-thirds majority in parliament while receiving only one-third of the national vote. The only other political party that passed the 10% threshold and gained representation in 2002 was the Republican People's Party (CHP).

This system is now placing all the parties of the fragmented opposition at a disadvantage vis-à-vis the AKP.

To overcome the 10% threshold problem, the center-left CHP and the smaller Democratic Left Party (DSP) merged their lists to run together under the CHP. However, unification efforts by the once-powerful conservative center-right Motherland Party (ANAP) and the True Path Party (DYP) under the new name of Democrat Party (DP) were unsuccessful, and ANAP withdrew from the elections process. This failure to produce a strong center-right alternative will probably prove to be the AKP's biggest advantage in the upcoming elections.

The AKP, for its part, included in its candidate list some well-known names from the center right, and even from the social democrats, with the aim of attracting votes from the nonreligious sector.

Among the CHP candidates are also some leading political figures from the center right, who joined the CHP believing it to be the only secular alternative that could challenge the AKP.

Besides the AKP and the CHP, there is the Nationalist Movement Party (MHP), which has been gaining ground due to the increasingly nationalist sentiment in the country. The MHP – and to some extent the CHP – are being strengthened by the AKP's failure to deal with increased terrorist activity by the PKK, which claims over 60 lives every month. It is also gaining ground due to the government's hesitation to allow the Turkish military to launch a cross-border incursion into northern Iraq where the PKK is based; and by the daily funerals of terror victims that turn into anti-government protests.

Another force emerging on the political scene is the representation of the Kurdish minority in Turkey. Members of the Democratic Society Party (DTP) – which followed the earlier, outlawed Kurdish parties DEP and DEHAP, and which is strong in Turkey's mainly Kurdish southeast – have decided to run in the upcoming elections as independent candidates, in order to avoid the 10% barrier. These independent candidates are expected to hold 25 to 30 seats in the next parliament.

Other political parties, such as the Young Party (GP) and the Democrat Party (DP), which may come close to the threshold with 7% to 9% of the votes, are not expected to gain legislative representation.

The Election Campaign

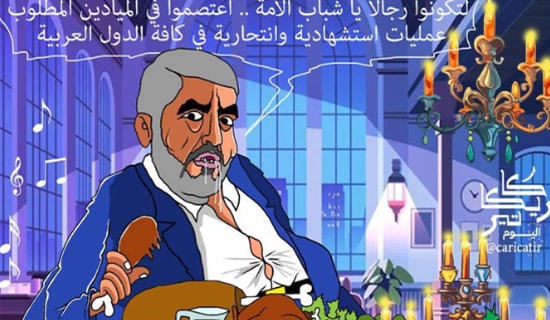

The AKP seems to be campaigning harder than its opponents, and is covering more of the country. Recently, it has begun to distribute, through its local branches and municipalities, "gift packages" in poorer neighborhoods nationwide, containing rice, wheat, beans, sugar, flour, oil, jam, pasta, soap, and so on, as well as one ton of coal per family for winter heating. Campaign buses are carrying loads of toys that are being distributed to children across the country by AKP candidates. These practices are being strongly criticized in the mainstream media as undemocratic means of "buying" votes.

Despite the fact that AKP is entering the upcoming elections as the largest as well as the ruling party, it is effectively depicting itself as a "victim," whose presidential candidate was "unjustly" rejected by the secular establishment because he is "religious" and "Muslim."

In its campaign, the AKP is also touting the economic growth that has taken place under its rule.[i]

A Consensus Presidential Candidate – Still a Contentious Issue

While Foreign Minister Gul continues to declare, in campaign forums, that he is still the presidential candidate, and is claiming that, judging by the reactions of the people, he would win if the presidency was to be decided by popular vote, Prime Minister Erdogan recently announced that he was ready to seek consensus with the opposition on a name. This decision was welcomed by all opposition leaders as the prime minister "finally accepting what was requested of him prior to the May stalemate." Had he agreed then to compromise, and worked with the opposition to find an impartial candidate, with respect for the constitutional principles of the republic – the crisis would have been avoided. Yet, another dispute has now ensued on the meaning of "consensus" and how to reach it.

Erdogan, who is by now probably aware of the fact that the AKP will not have the 367 seats necessary to elect a president by itself, said that he was ready to offer the opposition a few names as AKP candidates. However, Deniz Baykal, leader of the main opposition party CHP, responded that more names of the same kind would not be acceptable, and expressed his desire for the nomination of a nonpolitical, independent figure from outside the parliament.

If an agreement cannot be reached within the parliament that will be formed after the July 22 elections, and if the new parliament also fails to elect a president – or if the elections produce a CHP-MHP coalition and the AKP retaliates by boycotting the presidential vote – the parliament must again dissolve itself, and within 45 days again go to parliamentary elections.[ii]

Findings of Public Opinion Polls

Many polls and surveys are predicting an AKP win on July 22. With millions of votes bound to be thrown out because of the very high threshold that blocks representation by smaller parties, the AKP may indeed emerge as the first party. However, it is difficult to estimate the seat distribution in the next parliament.

According to a survey published in June by the reputable research and polling organization SONAR, the AKP may receive 40% of the votes, followed by the CHP with 20%. However, the findings also showed that a total of five parties – including the CHP, the MHP, the DP and the YP – would pass the 10% threshold and send representatives to the legislature. If the Kurdish DTP – now represented by independent candidates – fills 27-29 seats, as is indicated, the AKP might not be able to form a single-party government. The poll results point at 275-280 AKP seats (out of 550 parliamentary seats) in the event that five parties pass the threshold. This number would be 290-295, if four parties pass the threshold, and 320 if only three parties make it to parliament.

Analysis by the DHA (Dogan News Agency) without the DP and GP – since they are unlikely to pass the threshold – shows the following: AKP, 252-260 seats; CHP, 160-165 seats; MHP, 89-95 seats; and independents, 30-32 seats. With this distribution of seats, an expected CHP-MHP coalition cannot emerge, as both parties are sworn not to enter any coalition with AKP or Kurdish DTP representatives. This would give the AKP the opportunity to form the next government with active or passive support from DTP "independents."

While almost all the surveys indicate that three parties (AKP, CHP and MHP) will gain representation, some polls point to a head-to-head race between the AKP and the CHP – with each gaining about 30% of the votes. This would make the MHP the key party in forming the next coalition government.

*R. Krespin is the director of the Turkish Media Project.

[i] Although the official macroeconomic figures do indeed attest to an improved economy, many lower-income Turks have not shared in any of the benefits. The agriculture sector is suffering, and unemployment is at a record high, nearly 12%.

[ii] Wary of the possibility of having to go to multiple elections within the same year, all the parties may agree to bring to a referendum, in October, a constitutional change which would open the way for presidents to be elected by popular vote. A recent decision by the High Constitutional Court allows such a referendum.