The trial and execution of Shafiq Adas 75 years ago are fairly well documented. The purpose of this report is to shed light on the political atmosphere that prevailed in the Iraq that led to his tragic death, which ultimately triggered the mass emigration of Iraqi Jews.

For me, this story is also personal history, since I lived through these events. The events I'm describing occurred when I was 16 years old living in Basra, Iraq. I was not particularly close to Adas, but I saw him frequently, because a close relative of mine was Adas's right-hand man and sat next to him in the office of his car dealership (Adas and his brother Ibrahim were the sole agents in Iraq of Ford Motor Co., Michelin tires, and some other automotive companies). Almost every time I visited my relative, Mr. Adas was there, and we referred to him as Abu Zaki.

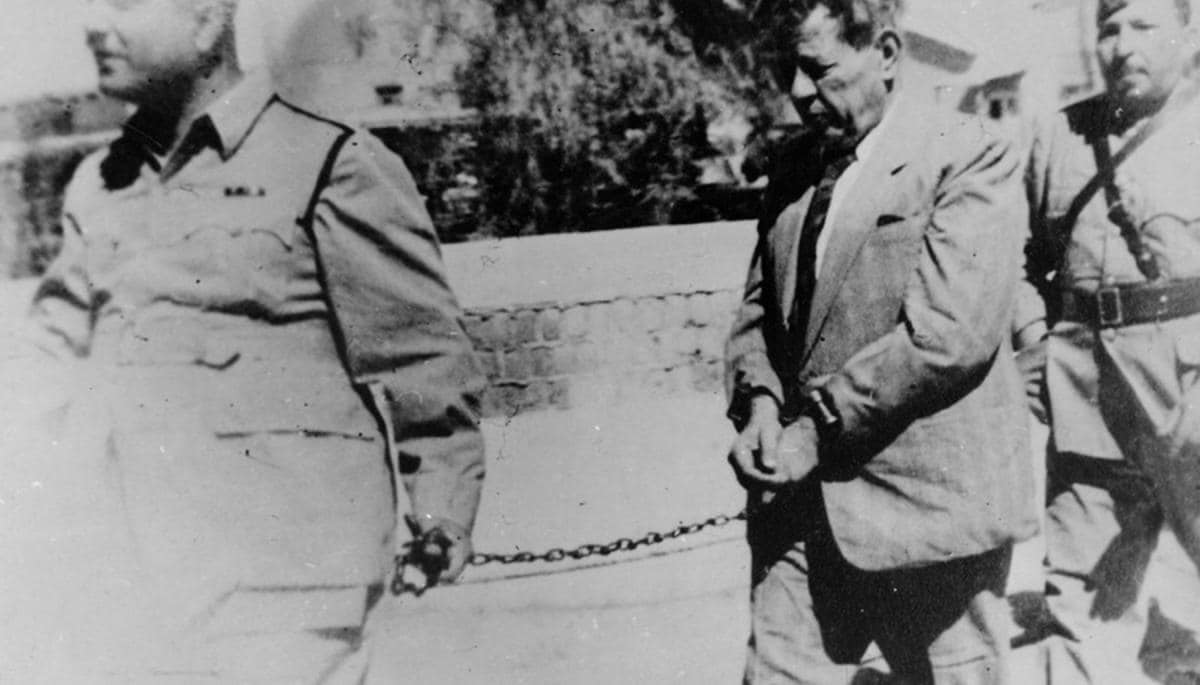

Shafiq Adas being led to the gallows on September 23, 1948.

Martial Law In Iraq

The Iraqi government announced martial law several hours before the establishment of Israel on May 14, 1948. The reason for the martial law was allegedly to protect the rear of the Iraqi army, which participated in the war against the nascent State of Israel.

Initially, the Jewish community felt that martial law would provide them with sufficient security and prevent the mob from harming like it had in 1941, when a pro-Nazi government instigated violence against the Jewish community, an event that is commonly referred to as the Farhud.[1] However, the martial law in fact created four military tribunals. One of them was located in Basra and it was charged with trying "spies, Zionists, and communists." The Jewish community in Iraq soon discovered that the martial law was not meant to protect the rear of the Iraqi military, but to harass and punish the Jewish community, particularly given the poor performance of the Iraqi army in the war.

The Jews Will Be Fuel For A Fire That Will Consume Them

Life for Jews in Iraq became increasingly dangerous. An illustrative example is that in 1948, Iraq had one national radio station, and multiple times a day it would broadcast the chant: "Tel Aviv, Tel Aviv will be roasted by flames and the Jews, the Jews will be the fuel."

تل ابيب تل ابيب سوف تصلى باللهيب واليهود اليهود سوف يكونونَ الوقود

Newspapers also published vicious antisemitic stories accusing Iraq's Jews of being a fifth column for the "Zionist entity," and Adas was singled out in these accusations, on the basis for unfounded allegations. The Istiqlal Party, with the support of Defense Minister Sadiq al-Bassam, launched demonstrations in Baghdad and Basra demanding that Adas be executed. The mouthpiece of the party was the ultra-nationalist newspaper Al-Istiqlal, under Editor-in-Chief Fa'iq al-Samara'i,[2] who led a vicious campaign against the Iraqi Jewish community and against Adas in particular.

An even more vicious newspaper was Al-Yaqdha, edited by Salman al-Safwani. It said that the Jews are Zionists and should not be treated as equal citizens. It was obsessed with Adas and similarly carried out a campaign against him. Ishaq Bar-Moshe relates in his book The Exit from Iraq that while carrying a copy of Al-Yaqdha, he walked into a shop, and the Armenian shopkeeper, an acquaintance of his, looked at the newspaper and asked: "So what are the headlines about Adas?"[3]

Forced Contributions Towards Rescuing Palestine

At the time, Iraq was awash with slogans about "Rescuing Palestine." Merchants, and particularly Jewish merchants, were forced to make large contributions for the rescue of Palestine. According to his former aide, Adas himself made a large contribution, as did all other Jewish merchants and businessmen.

As part of the Rescue Palestine campaign, the Iraqi government overprinted all postage and revenues stamps with the slogan "Rescue Palestine." The slogan was also printed over a variety of other tickets, including bus tickets.

SUPPORT OUR WORK

The Trial And Execution Of Shafiq Adas

The trial of Adas and the circumstances around the trial have been covered extensively by Iraqi writers in the post-Saddam era. Most impressive was the two volumes on the history of the Jews of Iraq written by Al-Ruba'i, which provide an extensive background to the trial and its aftermath.[4]

Adas was tried by a military tribunal under the presidency of Colonel Abdullah al-Na'sani for allegedly selling weapons to Zionists. In fact, what he sold, in partnership with Muslim businessmen, was scrap metal that was purchased from the British army, which maintained a strong presence in Iraq during WWII. "Witnesses" were brought to testify that Adas was guilty. Three well-known Muslim attorneys came down to Basra from Baghdad as defense attorneys, but al-Na'sani would not allow them to cross-examine any of the "witnesses" for the prosecution. Al-Na'sani also informed the lawyers that he would not accept witnesses for the defense. The lawyers decided to resign and left Adas defenseless.

The novelist Louie Abbas Hamza in his play The Carrier of the Umbrella describes the scene of the hanging quite dramatically:

"The verdict to hang Adas in Basra on September 23, 1948 was carried out in the early morning hours, which coincided with his 48th birthday. The cool early morning, or the darkness of the place or the awe of the gallows did not prevent thousands of people from Basra and elsewhere to gather, some since the evening before, to watch and celebrate the event. While the mob was celebrating the gruesome event, members of the Jewish community remained in their homes behind closed doors afraid, that a jubilant mob may turn violent."

According to Hamza, Adas was hanged not once, but twice, because the doctor in charge of the event claimed that Adas's heart was still beating after the first hanging, and three policemen had to lift him back up for a second hanging. This was in keeping with Iraqi criminal code that hanging must be carried out until death.

The hanging was carried out in front of a new house Adas was building, which ironically indicated that he had no intention of leaving Iraq. Some newspapers at the time claimed that the new house was meant to be the embassy of Israel. As to why an embassy will be in Basra and not in Baghdad the capital, the newspapers did not explain.

Documents unsealed by the British government 30 years after the event show that the British Ambassador to Iraq Sir Henry Mark wrote on September 20, 1948 to the Foreign Office in London that he met with Prime Minister Muzahim al-Pachachi and told him that the British system opposes the hanging of an innocent man. Al-Pachachi replied: "The matter was in the hands of the Regent and while the Regent opposes the hanging he believes that the national interest leaves him no choice."

Similarly, U.S. Ambassador to Iraq George Worth wrote to the State Department about his meeting with the Regent, who told him he could do nothing but approve the verdict. The Regent was under pressure by the army and key political actors, such that failing to approve the verdict would jeopardize the future of the Kingdom.

Al-Na'sani himself has his own version of the trial. According to one writer, al-Na'sani said to a circle of Jews with whom he had relations: "I have sentenced Adas to death because I was aware that the Iraqi people were seeking a sacrifice. If Adas were not hanged, they would have made pogroms against the Jews in Iraq, in revenge for the many Iraqi soldiers who died in the war. By hanging Adas I have saved the Jews from massacres."[5] Tragically, there may have been an element of truth to what al-Na'sani said.

Many years later, Jabbar Jamal al-Din, a poet and professor at Najaf University, wrote a beautiful eulogy:

"[Adas] is one of those who plants roses in the Spring Garden. [He] was an honorable merchant among the merchants of Iraq. His concern was not profit or loss, but rather his only concern was serving the oppressed and providing relief to the disadvantaged. Perhaps the truest characteristic added to this authentic Iraqi is that he is the creator who taps into the human heart and sings in our hearts songs of joy and tragedy."[6]

The hanging of Adas had a dramatic impact on the Jewish community in Iraq and provided the trigger for their seeking to leave. Mir Basri, a writer and historian and the last president of the Jewish community in Iraq, was quoted that the trial and execution of Adas demonstrated clearly that if even a Jew from a highly reputable family who was fully integrated within the Iraqi society, such as Adas, was not safe from punishment, clearly the Jews had no future in the country. [7] Anwar Shaul, a highly regarded Jewish Iraqi poet, also made the point that the execution of Adas intensified the efforts of the Jewish youth of Iraq to exit the country in all possible manners.[8]

Denationalization Of Iraq's Jewry

Less than two years after the hanging of Adas, the Iraqi parliament passed without deliberations in March 6, 1950 a law permitting the government to abrogate or denationalize the Iraqi nationality from any Jew who wanted to leave the country. Those who opted to leave were issued a laissez-passer with the inscription: "The bearer's Iraqi nationality has been annulled and he will absolutely not be granted entry to Iraq."

My own Iraqi laissez-passer with the stamp: "The bearer's Iraqi nationality has been annulled and he will absolutely not be granted entry to Iraq." Also stamped are the date I relinquished my Iraqi citizenship – June 13, 1950 – and the date of the exit from Iraq, April 9, 1951.

Some might argue that the law allowing Jews to renounce their nationality and leave the country was fair and reasonable, since those who did not wish to renounce their nationality could ostensibly remain. However, the government imposed economic measures tantamount to economic suffocation. All Jews working in government agencies and public entities were fired, and pressure was used to force them to resign in order to deny them their pensions. Access to bank accounts was restricted and all import licenses to Jews were denied. Travel outside Iraq was severely restricted, and universities denied entry to Jewish students. In short, the law allowing Jews to renounce their nationality and leave sounded voluntary the reality left the Jews no choice but depart.

This closed the long history of Jews coming from Babel to sovereign Iraq, and it opened the chapter about the Jewish refugees from Iraq to Israel.

For me personally, at age 18, with a secondary school diploma and neither prospect of higher education nor opportunities for a fruitful occupation or employment, I had no alternative to leaving Iraq. Like many in my generation, I relinquished my citizenship and left Iraq. I have no regrets, and never over the past seven decades have I considered seeking a "right of return" to Iraq.

*Dr. Raphaeli is a senior analyst emeritus at MEMRI.

[1] See the author’s MEMRI Daily Brief No. 290, The Dramatis Personae Behind The 1941 Farhud Pogrom In Baghdad – And Personal Recollections Of The Events, June 25, 2021.

[2] In the 1930s, Al-Samara’i had belonged in the 1930s to Al-Muthana Club, which was made up largely of pro-Nazi army officers and political figures, many of whom were behind the 1941 Farhud.

[3] Ishaq Bar-Moshe, The Exit from Iraq (Memoirs: 1945-1950), Jerusalem: Council of Sephardic Community, 1975, p.186.

[4] Nabil Abdul Amir al-Ruba’i, Lamahat Min Tarikh Yahood Al-Iraq, 859 BC -1973 CE, Hilla, Iraq, 2016. See my review of Volume 1 at Sephardic Horizons, Vol. 11, Issue 1, Winter 2021.

[5] Gourji C. Bekhor, Fascinating Life and Sensational Death. Israel: Peli Printed Works Ltd., 1990, p.99.

[6] Al-Ruba’i, op.cit. pp.212-213

[7] Fatten Muhii Muhsen, Mir Basri, Life History and Legacy, Baghdad, Mesopotamia House, 2010, p.138.

[8] Anwar Shaul, Story of My Life in Mesopotamia, Association of Iraqi University Graduates, Jerusalem, 1980, p.259.