This week, the Supreme Court is finally taking up cases concerning terrorist content on social media. For those who have been studying the issue, these cases have been a long time coming. Back in January 2015, an op-ed in Forbes titled "Terrorist Use Of U.S. Social Media Is A National Security Threat," Middle East Media Research Institute (MEMRI) President Yigal Carmon and I wrote about the need for the U.S. government to take action, noting that "solutions could require examination by constitutional law experts, and might need to go all the way to the Supreme Court."

MEMRI began monitoring terrorist use of the Internet in 2006. In 2010, we found that YouTube had emerged as the leading website for online jihad. I wrote multiple reports on the impact of the YouTube presence of Al-Qaeda and jihadi groups in the West, including the swiftly growing numbers of young Westerners who were being inspired to acts of terrorism by jihadi content.

On December 20, 2010, as these reports were being discussed in the media and on Capitol Hill, I met, at Google's invitation, with four senior Google representatives at the time, the head of Public Relations & Policy; senior Policy Manager; Senior Policy Counsel, and a fourth staff member, a free speech attorney – at the company's Washington, DC office to discuss MEMRI research on YouTube and jihadi videos.

Much of the meeting focused on videos of Al-Qaeda's Yemeni-American leader Anwar Al-Awlaki, the extremely influential jihadi sheikh who had provided personal guidance for the attacks carried out by Nadal Hasan and Umar Farouk Abdulmutallab in 2009. Hasan, an Army psychiatrist, killed 13 people in his shooting attack at Fort Hood, Texas, and Abdulmutallab attempted to blow up a Detroit-bound airliner on Christmas Day with explosives in his underwear. Al-Awlaki videos were known to have been viewed by jihadis who went on to perpetrate acts of terror – for example, the 2008 would-be Fort Dix bombers who were convicted of conspiring to kill American soldiers at the New Jersey army base. Also discussed at the meeting were other videos that were recommended as needing to be removed from YouTube.

Together with Google representatives, we looked at "Soldiers of Allah by Imam Anwar Al-Awlaki," a sermon by Al-Awlaki hosted on YouTube. I also demonstrated to them the issue that the current Supreme Court case is essentially about – how, when viewing jihadi videos, the platform's algorithm recommended similar videos from other YouTube accounts – including dozens more Al-Awlaki and other Al-Qaeda videos dealing specifically with jihad and featuring their iconography.

The YouTube representatives said that the "Soldiers of Allah" video would not be removed – because it was "a legitimate religious video" that is not "necessarily" related to jihad, even though it was by Al-Awlaki. According to the Google representatives, the algorithmic promotion of other jihadi videos was not a concern of theirs; it was not worth their time

Google's request for this meeting had come in the wake of bad press following the May 2010 London attempt by Roshonara Choudhry to murder MP Stephen Timms. She was found to have been downloading Al-Awlaki material – which media noted was widely available on YouTube – and, according to her own confession, had been radicalized by listening to his speeches there.

Reflecting the growing outrage about terrorist content on YouTube, in September 2010, U.S. Rep. Ted Poe, along with Reps. Ileana Ros-Lehtinen, Ed Royce, and Donald Manzullo, wrote a letter to the company, based on one of MEMRI's reports, expressing "deep concern" about "the increasing rise of terrorist groups using YouTube." They highlighted the fact that according to recent reports, "YouTube has become the largest clearinghouse of jihadi videos." The letter concluded by asking about YouTube's strategy for dealing with this content.

Under British and American pressure, YouTube told The New York Times that it had removed some Al-Awlaki videos featuring calls to jihad, as well as videos violating the site's guidelines prohibiting "bomb-making, hate speech, and incitement" to violence, or by "a member of a designated foreign terrorist organization" or promoting terrorist groups' interests. YouTube added that it would continue to remove such content but stressed that "material of a purely religious nature will remain on the site." It should be noted that all of Al-Awlaki's incitement was "purely religious."

It should be noted that even after his death in 2011, Al-Awlaki's online sermons continued to inspire attacks – including, according to terror experts, the San Bernardino, California shootings, in which 14 died; the Boston Marathon bombing, which killed three and wounded over 260 more; and the 2016 New York bombings, in which 29 were wounded.

Currently, the Supreme Court is hearing two terrorism-linked cases concerning Section 230 of the Communications Decency Act of 1996. One case, Gonzalez v. Google, is being brought by the family of Nohemi Gonzalez, a 23-year-old American citizen killed by ISIS in Paris in November 2015. The family contends that YouTube violated the Anti-Terrorism Act when its algorithms recommended ISIS-related content to users, and that the content recommended to users by algorithms shouldn't be protected by Section 230. The other case, Twitter v. Taamneh, considers if social media companies are liable for aiding and abetting international terrorism when terror groups use social media platforms.

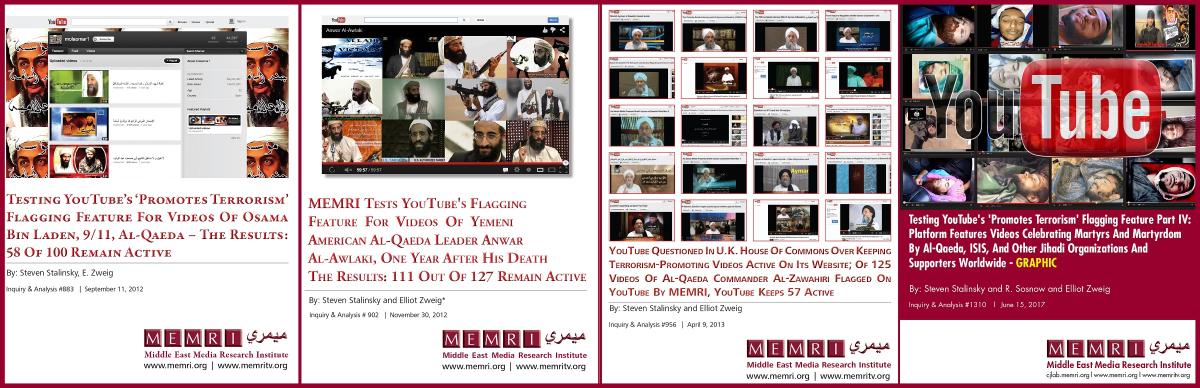

Following the December 2010 meeting, we continued to offer to help YouTube by identifying videos that incite violence and terrorist acts. YouTube's newly created flagging feature for content that "promotes terrorism" was tested throughout 2012 by the MEMRI Cyber & Jihad Lab (CJL), a flagship project which for over 15 years has tracked, researched, and analyzed terrorist activity in cyberspace, helping tech companies remove terrorist content.

After the original MEMRI reports, a 2012-2017 series of reports on the flagging of videos of Osama bin Laden, 9/11, Al-Qaeda, Al-Awlaki, and celebrations of terror attacks showed that majority of the content remained online.

Since then, YouTube has gotten a lot better at removing jihadi and terrorist material, and many of my suggestions made at that December 2010 meeting were implemented. However, while there are fewer jihadi videos in Arabic, the platform is hosting an increasing number of neo-Nazi, white supremacist, and other domestic terrorist content in many European languages. The absence of focus on removing such videos is allowing these movements to grow.

It is impossible to know how much damage has been done by allowing extremist content to continue to fester online in the eight years since our Forbes op-ed. While there is concern about what the court might rule, there is also a lot of potential for good overall outcomes for platforms besides those named in the lawsuits – for example, forcing the encrypted messaging app Telegram, widely favored by both jihadis and domestic extremists, to remove violent and extremist content.

Technology can help as well – algorithms can, in addition to serving up more similar content to viewers, help figure out whether content is free speech or violent incitement. Though imperfect, algorithms' accuracy will increase with time.

Over the past few weeks, there have been countless op-eds published about Section 230 and the future of the Internet who don’t really understand the dangers of terrorist content online. The vast majority of their authors have never seen the online terrorist content that I and my organization have been monitoring daily since 2006. I am also concerned that the Supreme Court justices are not well-informed enough in this matter to be able to make decisions concerning it. As Justice Elena Kagan herself said about the justices' self-confessed confusion, "We're a court. We really don't know about these things. You know, these are not like the nine greatest experts on the Internet."

Since 2015 (the events of Gonzalez v. Google) and 2017 (the events of Twitter v. Taamneh), the major social media companies have improved their monitoring of terrorist content. But they still must be held accountable for their inaction when terrorists had free rein on their platforms. What is needed are tech community industry standards providing for exclusion of companies, including app stores, which fail to follow the standards. What is needed even more is government oversight, with a biannual report showing the results of these companies' efforts in removing terrorist content, and harsh penalties for those companies that do not comply. It should also be noted that the heart of the issue is not part of today's lawsuits – that violent content inciting to killing can be wrapped in a religious context, and that freedom of speech must not cover calls to violence just because they come from a religious source.

*Steven Stalinsky is Executive Director of MEMRI (Middle East Media Research Institute), which actively works with Congress and tech companies to fight cyber jihad through its Jihad and Terrorism Threat Monitor.

Latest Posts