Introduction

One year after the outbreak of the popular protests that swept through the Arab world, and with the upcoming Arab League summit scheduled to take place in Baghdad on March 29, 2012, the Arab countries stand divided and bereft of real leadership. The revolutions have overthrown the previous balance of power, toppling regimes that once seemed indestructible and rendering other regimes increasingly unstable. Egypt and Syria, which in recent decades have been fighting for dominance in the Arab world, are now preoccupied with internal affairs. In Egypt, the Supreme Council of the Armed Forces, which has been running the country since the ouster of Hosni Mubarak, is grappling with economic and social problems and with an Islamist-dominated parliament, trying to keep its grip on the reins of power. The Syrian regime is fighting for its life by brutally suppressing protests against it, and has lost its legitimacy in the eyes of many in the Arab world and internationally.

The Arab revolutions have raised doubts as to whether the Arab League represents the Arab peoples or the Arab regimes that are struggling for survival. The uprisings in Tunisia and Egypt unfolded rapidly and thus left little room for a response from the Arab League. In the case of Libya, the Arab League was quick to condemn the Qadhafi regime, to recognize the Libyan Transitional National Council, and to hand the matter over to NATO, thereby acknowledging its inability to deal with the crisis. In the cases of Yemen and Bahrain, on the other hand, the Arab League failed to express any clear stance, and in the case of Syria, its conduct has been characterized by hesitancy, manifest in toothless decisions and the granting of repeated extensions to the regime.

It should be noted that the international community has likewise largely ignored the crisis in Yemen and Bahrain, and has yet to take a unified and firm decision on the Syrian crisis. The circumstances in Syria, very different from those in Libya, dictated a slower and more cautious approach by the Arab countries and the international community in this case. On the tactical level, the differences have to do with the scope of the protests in each country, the intensity of the regime's response to them, and the power of the local opposition. On the strategic level, the differences have to do with the geopolitical status of each country, the expected results of the regimes' collapse, and the nature of the alliances each regime formed with regional and international forces.

The leadership vacuum created by the collapse of the Mubarak regime and the plight of the Assad regime is being exploited by other countries, such as Qatar, Saudi Arabia, and Iraq, which are vying for leadership of the Arab world. To this end, they are launching initiatives to resolve the crises in various Arab countries and forming new axes and alliances, for instance by expanding the Gulf Cooperation Council (GCC) with an eye toward positioning it as an alternative to the Arab League.

At the same time, the withdrawal of the U.S. forces from Iraq, and the concern of the Gulf states, headed by Saudi Arabia, about the growing Iranian influence in Iraq and the possible formation of a Shi'ite front, have rekindled the Sunni-Shi'ite conflict in the Arab world. This conflict too is reflected in the Arab League – especially now, in the runup to the 23rd Arab League summit, which is scheduled to take place in Iraq (whose prime minister, Nouri Al-Maliki, is perceived by the Saudis as an ally of Iran).

These conflicts find expression both on the ground and in the diplomatic-political arena. When unrest broke out in Bahrain, Saudi Arabia sent a military force to this country to help its Sunni authorities suppress the Iran-supported protests. According to reports whose reliability cannot be confirmed, a similar situation currently exists in Syria as well: Iran is assisting the regime with weapons and fighters, while Iraq and the Gulf states are dispensing similar assistance to the Syrian opposition.

As for the political conflict, it is playing out mainly in the Arab League itself, whose status, power, and functioning are suffering as a result. These conflicts within the Arab League, and its declining status, are reflected in its handling of the Syrian crisis.

Arab League Powerless in Face of Syrian Crisis

In the first months after the outbreak of the Syrian revolution, the Arab League suffered an almost complete paralysis in the face of events there, despite repeated calls to intervene by elements in the Syrian opposition and the Arab world. Upon assuming office as Arab League secretary-general in June 2011, Nabil Al-Arabi endorsed the same position he had promoted as Foreign Minister of Egypt, which supported the Syrian regime.[1] After his meeting with President Assad on July 14, 2011, Al-Arabi said that the Arab League opposed interfering in the internal affairs of Arab countries. He stressed that only the Syrian people had the right to determine if their president had lost his legitimacy, and praised Assad's reform plan.[2] Al-Arabi was not the only one to take this stance. Many Arab countries, such as the UAE, Sudan, and Egypt continued ties with the Syrian regime and supported it despite the violent suppression of protests.[3]

From mid-August 2011, apparently following a change in Saudi Arabia's and Qatar's positions,[4] a shift began to be apparent in the position of the Arab League and its secretary-general, manifest by frequent meetings of the Arab Foreign Ministers Council and in an increase, albeit cautious and gradual, in the harshness of statements regarding the Syrian regime. On August 27, 2011, the Arab League formulated a detailed initiative to deal with the security and political aspects of the Syrian crisis in the short and long term, which included calls to end the violence and release prisoners; a demand for specific political reforms, such as revoking Article 8 of the Syrian Constitution, which grants a leadership monopoly to the Baath Party; and calls to establish a national unity government. However, the initiative did not include a call for Assad to resign, but rather to announce pluralistic presidential elections at the end of his term in 2014.[5] Syria rejected the initiative outright.

Two months later, the Arab League established a special committee to deal with the Syrian crisis. Headed by Qatar, the committee includes the foreign ministers of Algeria, Sudan, Oman, and Egypt, as well as the secretary-general of the Arab League. Its role is to liaise with the Syrian regime and opposition, and to formulate solutions for dealing with the crisis.[6]

On November 2, 2011, after lengthy discussions with the Syrian leadership, a "plan of action" was formulated, according to which Syria agreed to cease all types of violence, release the citizens arrested for participating in protests, clear residential areas of all "armed phenomena," and allow Arab League organizations and Arab and foreign media to move freely in its territory. After achieving real progress in implementing these obligations, the Foreign Ministers Council was to initiate contacts with the Syrian sides in advance of a national dialogue conference.[7] This plan actually represents a retreat in the Arab League's position and an acceptance of the Syrian regime's narrative – that the crisis is actually a confrontation between regime forces and an armed opposition, rather than a violent clampdown on nonviolent protesters. In fact, it can be interpreted as approving the regime's actions against those perceived armed opposition forces, and as granting it permission to escalate its battle against its opponents. The reason for these concessions may be the makeup of the committee, which clearly favored elements more sympathetic to the Assad regime – such as Algeria and Sudan, which are ruled by similar dictators, and Egypt.

In November 2011, the Arab League concluded that the Syrian regime was not implementing its obligations according to the plan of action, and decided, in an almost unprecedented move,[8] to ban Syrian delegations from meetings of the Arab League and of related organizations until Syria fulfilled these obligations in full, and to impose diplomatic and economic sanctions on Syria. Furthermore, it decided that if violence and killing continued, the Arab League secretary-general would appeal to the UN to take steps to end the bloodshed. This was the first time that the Arab League mentioned the possibility of involving non-Arab elements in dealing with a crisis. The Arab League did not spare its rod from opposition elements, and called on them to quickly formulate a united position on the transitional phase.[9]

Despite this harsh decision, presumably intended merely to pressure Syria, the Arab League continued its efforts to help Syria overcome the crisis by sending a delegation of observers, whose official task was to assess Assad's commitment to the Arab plan of action, but which, in practice, only gave Assad more time to suppress the protests. This delegation thus reflected the Arab League's incompetence and the Syrian regime's success in imposing at least some of its conditions, even when isolated and cornered.

The Observer Delegation to Syria – "The Last Nail in the Coffin" of the Arab League

According to various reports, Syria succeeded in pressuring the Arab League into making a number of alterations to the mission protocol of its observer delegation, which granted Syria considerable influence over the observers. For example, the Arab League agreed that the delegation would be limited to Arab representatives, rather than including observers from Arab, Islamic, and "friendly" countries, as the original protocol specified.[10] Moreover, the final draft of the protocol specified that the observer delegation would coordinate its activities with the Syrian regime; that it would submit periodical reports to both the Arab League and the Syrian government before submitting its findings to the Arab League's Foreign Ministers Council; and that Syria would have the right to refuse an extension of the delegation's mission.[11]

Even before it set to work, the delegation faced numerous problems, such as the Arab League's inexperience in managing such a task, and the choice as delegation leader of Mustafa Al-Dabi, a senior Sudanese military commander and presidential representative to Darfur, which raised eyebrows among international human rights organizations and raised serious doubts regarding the delegation's credibility. Furthermore, the number of observers was insufficient considering the magnitude of the crisis and the size of Syria; some of the observers were untrained in conducting such missions; the observers were required to coordinate their movements with the regime, whose forces accompanied them almost everywhere they went, and, in fact, oversaw their activity; and the delegation was authorized only to oversee the Syrian regime's implementation of the plan of action to which Syria had committed. Qatari Prime Minister Hamad bin Jassem Aal Thani admitted that "one of the problems was that we [the delegation] went [to Syria] not in order to stop the killing, but [only] to observe."[12]

Nor did the situation on the ground, once the observers arrived in Syria, help them accomplish their mission. Just one day after the arrival of the preliminary delegation, two large-scale bombings – the first since the outbreak of the uprising – occurred outside military intelligence facilities in Damascus, giving rise to mutual accusations between the regime and the opposition. Moreover, the death toll among Syrian protestors rose more rapidly during the delegation's stay than it had prior to the delegation's arrival. Indeed, it seems that the regime exploited the delegation's presence to step up its suppression of the protests, on the pretext of implementing the clause requiring it to "remove all armed phenomena from the cities and residential areas."

The delegation was not sympathetically covered in the Arab media, and the Arab press published numerous articles criticizing its conduct. For instance, Raja Taleb, columnist for the Jordanian government daily Al-Rai, wrote: "There is no need for observers to verify the killing perpetrated every day and every moment throughout Syria. This death is documented by photographs, voices, names, and dates."[13] Columnist Sa'd Al-Mu'atish expressed disappointment over the appointment of Al-Dabi, who he said "has proven incapable of seeing further than the tip of his own nose, and needs an observer to oversee him and discover whom he meets and who is issuing his orders..."[14] Senior journalist Daoud Al-Shiryan, a columnist for the London-based Saudi daily Al-Hayat, warned that the delegation's mission was "likely to be the last nail in the coffin of the Arab League's credibility and role."[15]

Syrian security chief leading blind "observers"[16]

A week after announcing its decision to extend the observer delegation's mission, the Arab League reversed the decision and halted the mission, saying that "the Syrian government [had] resorted to escalating the military option."[17]

On February 12, 2012, in a decision that reflected its helplessness in handling the Syrian crisis, the Arab League's Council of Foreign Ministers called on the UN Security Council to raise a joint peacekeeping force, consisting of troops from the UN and the Arab states, that would oversee a ceasefire in Syria, and on the international community to cease diplomatic cooperation with the Assad regime and to grant the Syrian opposition all possible diplomatic and material aid.[18]

Another step taken by the Arab League, in collaboration with the UN, in an effort to resolve the Syrian crisis was the February 23, 2012 appointment of former UN secretary-general Kofi Annan as an envoy to Syria on behalf of both bodies (though Assad seems to regard him as a UN envoy only). The Lebanese daily Al-Safir reported that, in one of their meetings during Annan's visit to Damascus on March 10-11, 2012, Assad said that, as far as he was concerned, the Arab League no longer existed, and that he had removed it from his foreign and domestic considerations and would continue to do so until it changed its decisions and position on the Syrian crisis.[19]

The Arab League's Failure to Deal with the Syrian Crisis

During the months in which the Arab League attempted to deal with the Syrian crisis, many failings were revealed in its function, and much criticism was leveled at it in Arab media; so much so that its legitimacy was compromised.

A. Inability to Enforce Resolutions

Throughout the crisis, the Syrian leadership fooled the Arab League by promising to enact reforms and supposedly accepting various initiatives in an attempt to buy time to crush the protests. In practice, the Syrian regime, which enjoys Russian-Chinese-Iranian support, flagrantly ignored the Arab League's resolutions and calls to enact reforms. Only the fear of losing some of the aforementioned support led the regime to accept some of the Arab initiatives, as happened in the case of the observer delegation, when the regime agreed to sign the delegation's protocol under Russian pressure.[20]

The Arab League resolutions regarding Syria were disregarded not only by Syria itself. The resolution to impose sanctions on Syria remained symbolic since all of Syria's neighbors - including Jordan, which supported the resolution – failed to implement it, a fact that was met with understanding by the Arab League secretary-general. Addressing Lebanon's statement that it would not implement the resolution, Al-Arabi said that Lebanon had a special status, which was appreciated by all Arab countries.[21] Some countries even announced explicitly that they would not implement the resolution. Iraq announced that it would increase trade with Syria[22]; Algeria announced that "our ambassador in Syria and the Syrian Ambassador to Algeria are welcome in their respective countries, and will continue to operate in a spirit of brotherhood and positivity... Now, more than ever, we must tighten relations with the Syrian government in order to implement the plan that was approved by the Arab League..."[23]

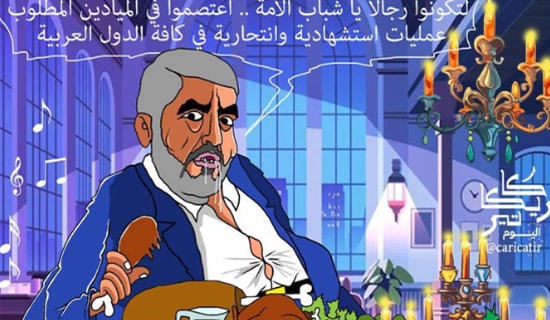

The Arab League bemoans the massacre in Homs from afar[24]

B. Turning to Arab Elements to Mediate Between the Arab League and the Syrian Regime

As part of the efforts to solve the Syrian crisis, the Arab League secretary-general appealed to various elements in the Arab world – such as Iraq, Hamas Political Bureau Chief Khaled Mash'al, and former IAEA chief Mohamed ElBaradei – to mediate between the Arab League and the Syrian regime. These appeals were perceived as reflecting the incompetence of the Arab League and its head in resolving the crisis. Thus, Iraqi Foreign Minister Hoshyar Zebari said that the Arab League's appeal to his country reflected its weakness, after its initiative to resolve the crisis had reached a dead end, versus the powerful position of Iraq, which has ties with both the Syrian regime and opposition.[25]

C. Claims of Arab League Collaboration with the Syrian Regime

The Arab League's conduct gave rise to harsh accusations that this it was sabotaging solutions to the Syrian crisis, intentionally or unintentionally, and even collaborating with the Syrian regime. This criticism was voiced especially in the newspapers of Saudi Arabia, whose government adopted a clear anti-Syrian line. In his column in the daily Al-Sharq Al-Awsat, 'Abd Al-Rahman Al-Rashed called the Arab League "a sword of the Syrian regime, which... thwarted international initiatives to resolve the crisis, whether knowingly or out of ignorance... and prolonged [the handling of] the crisis by months... Instead of being the racehorse to save the Syrian people, it has become Assad's Trojan horse, which he used to thwart the European initiatives... If the Arab League had done nothing, the results would have been better..."[26] After the publication of the observer delegation report, the Saudi government daily Al-Yawm accused the Arab League of assisting "the Syrian killing machine."[27]

D. Calls to Internationalize the Crisis and Arm the Opposition

In the face of the Arab League's incompetence, Al-Quds Al-Arabi editor Abd Al-Bari 'Atwan advised the Syrian people to rely on its own resources rather than on the Arab League.[28] Al-Sharq Al-Awsat editor Tariq Alhomayed called to immediately arm the Syrian opposition.[29] Many articles in Arab press called on the Arab League to withdraw from dealing with the Syrian crisis and let others take its place. In his column in the Jordanian daily Al-Dustour, Hilmi Al-Asmar called on the Arab League, "[Do not] try and handle a case that is too big for you. You have failed to solve problems far simpler than the Syrian problem..."[30] Several columnists demanded to apply the solution that was used in Libya, and hand the matter over to NATO. Thus, former Jordanian information minister Saleh Al-Qallab called in an article in Al-Rai to ask for military intervention by the UN or NATO, "without whose intervention in Libya, Qadhafi would [still] be sitting on the skulls of hundreds of thousands of Libyans."[31]

E. The Arab League Internationalizes the Crisis

Some six months after initiating its attempts to solve the Syrian crisis, the Arab League secretary-general asked the UN Security Council to adopt a resolution demanding all parties to immediately cease hostilities and protect the Syrian citizens.[32] On February 12, 2012, the Arab League called on the Security Council to send joint UN-Arab forces to oversee a ceasefire in Syria.[33] On February 24, 2012, former UN secretary-general Kofi Annan was appointed special envoy to Syria on behalf of the UN and the Arab League. Though the Arab League repeatedly stressed that it was not relinquishing an Arab solution to the crisis, these calls and steps were in fact an admission of its failure and the failure of the Arab solution, and a move towards internationalizing the Syrian crisis.

The Schisms within the Arab League

The Arab League's handling of the Syrian crisis exposed the existence of two new main camps in the Arab world: the first, which opposes Assad's regime and works to oust him, is led by the GCC, especially Saudi Arabia and Qatar; and the second, pro-Syrian, is led by Iraq, which is under Iranian influence and is operating according to Iran's guidance on this matter. In fact, the disagreements regarding Syria reflect the resurfacing of the struggle for dominance of the Arab world, as well as the struggle between the Saudi-led Sunni camp and the Shi'ite camp led by Iran (via Iraq). These struggles are taking place on the backs of the Arab League and the Syrian crisis, and were also partly responsible for the Arab League's incompetence.

1. The Sunni-Shi'ite Struggle

Saudi Arabia's battle against Iranian influence in the Arab world, which is rooted in the historical Sunni-Shi'ite struggle, was expressed twice in the first decade of the 21st century: in the Lebanon war of 2006, and the Gaza War of 2009.[34] The new arena for this struggle is the Arab League.

The upcoming Arab summit is supposed to take place in Iraq, which has close ties with Iran, and whose prime minister, Nouri Al-Maliki, is a Shi'ite. According to the Arab League regulations, the hosting of the summit in Baghdad also means that Iraq will assume the organization's rotating presidency. It was recently reported that the Gulf states object to holding the summit in Baghdad in light of Iraq's position on the Syrian crisis and following allegations that the Sunni minority in Iraq is being persecuted by Al-Maliki's government. Qassem Al-A'raji, a member of the Security and Defense Committee in the Iraqi parliament, claimed that the Gulf states are attempting to move the summit to Saudi Arabia, accusing them of acting from sectarian motives.[35]

The Jordanian daily Al-Arab Al-Yawm reported that the Gulf states threatened to move the summit to Riyadh and dedicate it to the Syrian issue unless Al-Maliki adopted their position vis-à-vis the Assad regime and true reconciliation was achieved between the various forces in Iraq.[36] 'Abd Al-Rahman Al-Rashed wrote in his column in Al-Sharq Al-Awsat: "Honestly, if [Prime Minister Nouri] Al-Maliki does not heed the feelings of most Arabs, we don't want the summit to take place in Baghdad this year. If it takes place there, he will probably bury the Arab League, just as he buried the new democracy in Iraq..." He explained that transferring the presidency of the Arab League from Qatar, which takes a firm position against the Syrian regime, to Iraq, the Syrian-regime's only ally in the Arab world, would lead to adopting a pro-Syrian policy.

While it is possible that the Gulf states fear the rotation of the Arab League presidency from Qatar to Iraq due to the impact it would have on the Syrian crisis, it seems that the real reason is deeper and is tied to their fear of Iran's influence over Iraq, and through it, over the Arab world. Saudi Foreign Minister Saud Al-Faisal said that there are points of dispute that could thwart the success of the summit, chief among them Iran's flagrant interference in Iraq.[37] Al-Sharq Al-Awsat editor Tariq Alhomayed warned that it is dangerous to trust the Arab League to solve the Syrian crisis "when the presidency of the Arab League will be subject to Nouri Al-Maliki's government... especially if we remember the Iranian statements regarding Iraq being part of Iran's sphere of influence..."[38] Harsher comments were made by Dr. Safouq Al-Shimri in his column in the Saudi government daily Al-Riyadh: "Iran possibly stands to gain the most from the rotation of the Arab League presidency [from Qatar to Iraq]. I will not be exaggerating if I said [Iran] would benefit more than Iraq itself. The current government in Iraq is nothing but an Iranian proxy that carries out Persian orders without question... Woe unto us if Iraq, in its current state, becomes president of the Arab League. I wouldn't be surprised if any country wanting something from the Arab League would be referred to the Iranian embassy... Arabs must not give Iran, or the current Iraqi government, any opportunity to control the common Arab action, whether by postponing the summit or by lowering the level of representation to a minimum..."[39]

It should be mentioned that, to date, there have been no reports of a Gulf decision to boycott the Arab Summit in Baghdad, although the rank of the Gulf delegates who will attend the summit is still unclear. Saudi Arabia recently announced that, for the first time since 1990, it has appointed a (non-resident) ambassador in Iraq "in order to tighten the good relations between the countries and the peoples."[40]

2. Struggle for Leadership

Saudi Arabia Attempts to Dwarf Arab League

The ouster of Hosni Mubarak in Egypt, and Bashar Al-Assad's struggle to maintain his regime in Syria, have presented Saudi Arabia with a unique opportunity to assert itself as a leading power in the Arab, and specifically Sunni, world. Such aspirations are nothing new for Saudi Arabia, but it seem that now, more than in the past, it has a real chance to bring them to fruition. To this end, the kingdom is taking advantage of the GCC, which it heads, as well as the Arab League, and is acting on several levels: First, taking advantage of the GCC's weight as the largest bloc in the Arab League, it is attempting to impose its will on this organization. For example, it has managed (with Qatar's cooperation) to impose harsher resolutions against the Syrian regime, such as suspending the latter's membership in the Arab League and leveling economic and diplomatic sanctions against it.

Second, with Qatar's help, and advancing its own status at the expense of the Arab League, Saudi Arabia has promoted Arab League resolutions and steps to internationalize the crisis in Syria – a de facto admission of the League's failure to handle this crisis. Saudi Arabia has also worked to form an alternative Arab body in which it would have a central and uncontestable role. This attempt was manifest in King 'Abdallah's initiative to create a coalition of Sunni monarchies by adding Jordan and Morocco to the GCC, thus forming a new inter-Arab political body to replace the Arab League. When this failed, King 'Abdallah launched a successful campaign to tighten cooperation among the GCC states. These moves are also meant to boost Saudi Arabia's maneuverability vis-à-vis Iran.[41]

Accordingly, many Saudis voiced disappointment and harsh criticism over the Arab League's conduct, while heaping praises upon the GCC. For example, Saudi Defense Minister Emir Salman bin 'Abd Al-'Aziz said that the GCC was, at present, the sole successful Arab organization.[42] Tariq Alhomayed, editor of the Saudi daily Al-Sharq Al-Awsat, went even further, expressing desperation over the Arab League's inability to handle the Syrian crisis, and calling for the establishment of a new regional alliance to comprise the Gulf states and other Arab countries, as well as Turkey and other non-Arab countries.[43]

Throughout the Syrian crisis, the GCC, led by Saudi Arabia, advanced several successful moves outside of the Arab League, as part of its aspirations to become an alternative to the League and assume a leading role in the Arab world. For instance, on March 2, 2012, it was reported that the GCC plans to hold a meeting with Russia's foreign minister to express its disappointment over the Russian stance on the Syrian crisis, and to call on Russia to adopt a different stance, in line with the aspirations of the Syrian people.[44] A clear mark of the GCC's success came when its August 6, 2011 announcement condemning the Syrian regime's use of excessive violence and calling for an immediate end to the bloodshed and the implementation of serious reforms[45] was endorsed, albeit reservedly, by the Arab League secretary-general and by additional Arab countries, like Egypt.

On February 7, 2012, the GCC announced that its member states would recall their ambassadors from Syria and expel the Syrian representatives from their territory.[46] It should be noted that many of these states recalled their ambassadors from Syria months ago, most notably Qatar, Saudi Arabia, and Kuwait – so the novelty in the announcement was that it came from the GCC as an organization, rather than from its individual member states, and that it called for the expulsion of the Syrian ambassadors. On February 19, Egypt announced that its ambassador to Damascus would not return to Syria after a vacation at home.[47]

Qatar Aspiring to Status and Prestige

Qatar was first in the Arab world to take up a harsh line against the Assad regime, as evident in Al-Jazeera TV's coverage of the events in Syria and in editorials published in Qatari government dailies.[48] Criticism of the regime later moved to official circles, led by Qatari Prime Minister and Foreign Minister Hamad bin Jassem Aal Thani, who took a firm position against the Syrian regime in both the Arab and international arenas.

Qatar's stance signals a fundamental shift in its policy, following years of close relations between the two countries, both of which belong to the resistance camp led by Iran and Syria. This shift may be part of an attempt on Qatar's part to win the sympathy of the Arab street and attain a leadership role in the Arab world by promoting initiatives to resolve the crisis. Qatar has apparently grasped that the balance of powers in the Arab world is changing, and that the time has come for it to cut itself loose from Syria and Iran.

Notwithstanding its membership in the GCC, it is unclear to what extent Qatar is party to Saudi Arabia's campaign to position this body as an alternative to the Arab League, considering that, in such a scenario, Qatar would be secondary to Saudi Arabia, whereas within the Arab League, it has greater maneuverability to move from one camp to another in order to maintain its influence in the Arab world.

Iraq Exploiting the Arab League to Legitimize Shi'ite Rule and Upgrade Its Status

The 23rd Arab League summit, slated to be held in March in Baghdad, will mark the first official Arab recognition of Nouri Al-Maliki's government, after the League declined in recent years to hold the summit in Iraq due to "security and political" concerns. The Iraqi government is therefore investing great financial, logistic, and diplomatic efforts in ensuring the summit's success. As part of these efforts, Iraq is taking pains to secure maximal participation of the Arab, and particularly the Gulf, states. This effort recently led Iraq to change its policy toward Syria, whereas previously it was the Syrian regime's primary source of support in the Arab world – as evident, for instance, in Iraq's opposition to the Saudi-Qatari line and its rejection of the Arab League's economic sanctions against Syria.

It would seem that Iraq is now prepared to align itself more closely with the Saudi line on Syria, at least tactically, in order to gain legitimacy in the Arab world. This shift in policy may also reflect a willingness on the part of Iran to let Al-Maliki's government gain legitimacy in the Arab world – a situation that would benefit Tehran as well as Baghdad. This may explain the dearth of Iranian criticism over Iraq's shift on Syria, as opposed to its loud objections to a similar shift by Hamas.[49]

Iraq's policy shift was manifest in a number of steps it has taken recently, which can be interpreted as an attempt to mollify the Gulf states and to ensure that the Arab League summit take place in Baghdad. For instance, in a January 30, 2012 meeting with Arab League Deputy Secretary-General Ahmad bin Hali, Prime Minister Al-Maliki declared his support for the latest Arab initiative calling on Assad to empower his vice-president, Farouq Al-Shara', to cooperate with a national unity government in facilitating a transitional stage.[50] Iraq likewise supported the Arab League's recent call, initiated by Saudi Arabia and Qatar, to establish a joint Arab and international peacekeeping force and provide diplomatic and material aid to the Syrian opposition.

On February 11, Iraqi government spokesman 'Ali Al-Dabbagh announced that Iraq's president had sent out official invitations to the Arab heads of state to participate in the Arab League summit in Baghdad, excepting Syria.[51] Iraqi Prime Minister Al-Maliki, however, expressed his hope that Assad would be present at the summit, while emphasizing that his country would remain committed to the resolutions of the Arab League.[52]

Egypt Striving to Maintain Its Supremacy

Apart from these camps, it is important to examine the stance of post-Mubarak Egypt. The country's Supreme Council of the Armed Forces (SCAF), which took up the reins of power after Mubarak's ouster, is currently more preoccupied with domestic concerns than with events in the Arab world at large, as evident in Egypt's attitude toward the Syrian crisis.

Since August 2011, the new Egyptian regime has not launched any initiatives of its own concerning the events in Syria, but has limited itself to responding to the initiatives of Qatar and Saudi Arabia. As might be expected of a regime that rose to power as the result of a popular revolution against its predecessor, Egypt has tried to portray itself as backing the demands of the Syrian people, while expressing reservations over the Saudi-Qatari line and calling for a more moderate policy vis-à-vis the Assad regime. This may indicate the SCAF's desire to depart from Egypt's Mubarak-era foreign policy, which saw Saudi Arabia as its primary ally in the Arab world and Syria as a chief adversary. Egypt's reservation over the Saudi-Qatari stance can also be explained by tension between Egypt and Qatar, which, according to reports of uncertain credibility, are rooted in Qatari interference in Egypt's domestic affairs, both by allegedly funding Egyptian political parties and through Al-Jazeera's coverage of the Egyptian revolution and its aftermath.[53] Egypt, moreover, is wary of a Qatari takeover of the Arab League,[54] as depicted in an article by Egyptian columnist Sa'id Al-Lawandi, who wrote that it would be "very regrettable if the Arab League were allowed to be swallowed up by a country as small as Qatar."[55]

Recently, Egypt has taken up a somewhat harsher stance vis-à-vis the Syrian regime.[56] According to reports, some Muslim Brotherhood-led committees in the Egyptian parliament have formulated an Egyptian initiative on Syria "with the foreign ministry's understanding,"[57] and another Egyptian plan to resolve the crisis in Syria has been submitted to the UN Human Rights Council.[58] These initiatives, however, are not particularly groundbreaking or creative. The parliamentary committees' initiative calls upon Egypt, Russia, China, Iran, and Turkey to devise a plan for stopping the violence in Syria and paving the way for a nonviolent transition of power, whereas the initiative submitted to the UN calls for the immediate and full implementation of the Arab League's resolutions, and opposes foreign, including military, intervention. These moves, then, seem to be chiefly aimed at presenting Egypt as an initiator, in order to maintain its traditional role as a leading Arab country. It should be noted that these two Egyptian plans were not presented before the Arab League, seemingly because Egypt assumed they would not receive majority approval, considering that they deviate from the Saudi-Qatari line and remove Saudi Arabia and Qatar from the sphere of influence.

Another possible explanation for Egypt's tougher stance on the Syrian regime is the increasing protest in Egypt over the country's policy vis-à-vis Syria.[59]

* N. Mozes is a research fellow at MEMRI.

[1] While serving as Egyptian foreign minister, Al-Arabi said that Syria's stability was part of Egyptian and Arab national security and that his country was working to thwart a severe anti-Syrian resolution in the UN Security Council. See MEMRI Special Dispatch Series No. 3926, "Syrian Journalist: Egypt's Foreign Minister Supports the Syrian Regime," June 19, 2011, Syrian Journalist: Egypt's Foreign Minister Supports the Syrian Regime.

[2] SANA (Syria), July 14, 2011.

[3] In July 2011, Egyptian Ambassador to Syria Shawqi Isma'il predicted that relations between the two countries would tighten following the Egyptian revolution. According to him, one of the main goals of the revolution was to tighten relations with other Arab countries and restore Egypt's Arab role. He expressed confidence that Syria would emerge empowered from the crisis thanks to its peoples' awareness and its president's wisdom. Al-Ba'th (Syria), July 31, 2011. In June 2011, following a meeting with Syrian Foreign Minister Walid Al-Mu'alem, Abu Dhabi Crown Prince Muhammad bin Zayed Al Nahyan expressed, on behalf of the UAE, his support for Syria and for President Assad's reform plan, as well as a desire to assist Syria economically. Al-Watan (Syria), June 6, 2011. In early July 2011, Saudi Arabia was still distancing itself from the events, stressing that it did not interfere in the matters of others, and made do with expressing sorrow at the deaths of civilians and voicing general calls to end the bloodshed and enact reforms. Al-Sharq Al-Awsat (London), July 6, 2011.

[4] See MEMRI Inquiry & Analysis Series No. 725, "Gulf and Arab States Break Silence over Syria Crisis," August 17, 2011, Gulf and Arab States Break Silence over Syria Crisis.

[5] Al-Hayat (London), September 6, 2011. It should be mentioned that the Arab League website does not detail the initiative, but only mentions it exists.

[6] http://www.arableagueonline.org, October 16, 2011.

[7] http://www.arableagueonline.org, November 2, 2011.

[8] The only country ever suspended from the Arab League before this is Egypt, whose membership was suspended after it signed the peace agreement with Israel.

[9] http://www.arableagueonline.org, November 12, 2011.

[10] Al-Rai (Kuwait), December 13, 2012.

[11] Arableagueonline.org, December 19, 2011.

[12] Ammonnews.net, January 5, 2012.

[13] Al-Rai (Jordan), January 2, 2012.

[14] Al-Rai Al-'Am (Kuwait), January 4, 2012.

[15] Al-Hayat (London), January 2, 2012.

[16] Aljazeera.net, January 2, 2012.

[17] Arableagueonline.org, January 28, 2011.

[20] SANA (Syria), December 20, 2011.

[21] Al-Rai (Kuwait), December 13, 2011.

[22] Al-Watan (Syria), January 12, 2012.

[23] Al-Sharq Al-Awsat (London), November 14, 2011.

[24] Al-Arab (Qatar), February 26, 2012.

[25] Al-Sharq Al-Awsat (London), December 11, 2011.

[26] Al-Sharq Al-Awsat (London), February 11, 2012.

[27] Al-Yawm (Saudi Arabia), February 16, 2012.

[28] Al-Quds Al-Arabi (London), February 15, 2012.

[29] Al-Sharq Al-Awsat (London), February 15, 2012.

[30] Al-Dustour (Jordan), January 8, 2012.

[31] Al-Rai (Jordan), February 16, 2012.

[32] http://www.arableagueonline.org, January 31, 2012.

[33] http://www.arableagueonline.org, February 12, 2012.

[34] See MEMRI Inquiry & Analysis Series No. 492, "An Escalating Regional Cold War – Part I: The 2009 Gaza War," February 2, 2009, An Escalating Regional Cold War – Part I: The 2009 Gaza War.

[35] http://www.albaghdadianews.com, February 18, 2012.

[36] Al-Arab Al-Yawm (Jordan), February 22, 2012.

[37] Al-Sharq Al-Awsat (London), March 5, 2012.

[38] Al-Sharq Al-Awsat (London), January 23, 2012.

[39] Al-Riyadh (Saudi Arabia), February 21, 2012.

[40] Al-Watan (Saudi Arabia), February 22, 2012.

[41] See MEMRI Inquiry & Analysis Series Report No.696, "Addition of Jordan and Morocco to Gulf Cooperation Council – A New Sunni Arab Alignment Against Iran," June 15, 2011, Addition of Jordan and Morocco to Gulf Cooperation Council – A New Sunni Arab Alignment Against Iran.

[42] Al-Watan (Saudi Arabia), February 5, 2012.

[43] Al-Sharq Al-Awsat (London), January 23, 2012.

[44] Al-Riyadh (Saudi Arabia), March 2, 2012.

[45] Alarabiya.net, August 6, 2011.

[46] Al-Sharq Al-Awsat (London), February 8, 2012.

[47] Al-Hayat (Saudi Arabia), February 19, 2012.

[48] See MEMRI Inquiry & Analysis Series Report No.688, "The Resistance Camp Abandons Syrian President Bashar Al-Assad and His Regime," May 13, 2011, The Resistance Camp Abandons Syrian President Bashar Al-Assad and His Regime.

[49] See MEMRI Inquiry & Analysis Series Report No. 808, " Iran-Hamas Crisis: Iran Accuses Hamas of Relinquishing the Path of Resistance ," March 9, 2012, Iran-Hamas Crisis: Iran Accuses Hamas of Relinquishing the Path of Resistance.

[50] Al-Watan (Syria), January 31, 2012.

[51] Shafaaq.com, February 11, 2012.

[52] Al-Quds Al-Arabi (London), February 19, 2012.

[53] According to the Lebanese daily Al-Akhbar, the Egyptian regime has knowledge of Qatari interference in Egypt's recent parliamentary elections. Al-Akhbar (Lebanon), November 16, 2011. Claims that elements in Qatar and Saudi Arabia are funding several Islamist parties in Egypt were raised by Dr. S'ad Al-Din Ibrahim, director of the Ibn Khaldoun Center in Cairo. Al-Masri Al-Yawm (Egypt), December 17, 2011. The implicated political parties denied these claims. Al-Ahram (Egypt), January 13, 2012. The Coalition of the Popular Committees organized a demonstration outside the Qatari embassy in Cairo, demanding the country be suspended from the Arab League in light of what it called Al-Jazeera TV's incitement campaign, which it said aimed "to harm the honor of Egypt and [undermine] its interests." Al-Ahram (Egypt), January 13, 2012.

[54] The Lebanese Al-Akhbar reported that the Egyptian regime was furious over Qatar's efforts to lead the Arab world, and had instructed its foreign ministry to prevent it from taking over the Arab League. Al-Akhbar (Lebanon), November 16, 2011.

[55] Al-Ahram (Egypt), December 26, 2012.

[56] On February 15, 2012, Egypt condemned the "unacceptable" escalation of violence in Homs, and called on the Syrian regime to effect immediate changes so as to prevent an all-out explosion. Al-Masri Al-Yawm (Egypt), February 15, 2012. As mentioned, on February 19, Egypt announced that the country's ambassador to Damascus, who was on a visit to his homeland, would not return to Syria. Al-Hayat (Saudi Arabia), February 19, 2012.

[57] http://gate.ahram.org.eg, February 28, 2012.

[58] Ikhwanonline.com, February 28, 2012.

[59] On February 6, 2012, the Egyptian parliament, which is headed by the Muslim Brotherhood, announced a suspension of relations with the Syrian parliament. Syria-news.com, February 7, 2012. On February 17, thousands of Egyptians protested outside the Syrian embassy in Cairo, demanding that the Egyptian regime expel the Syrian ambassador. The Muslim Brotherhood's Freedom and Justice party called to sever ties with the Assad's "blood regime," and to aid the Syrian opposition. Al-Hayat (London), February 17, 2012.