We seem to be living that famous quote, falsely attributed to Lenin, that "there are decades when nothing happens and there are weeks when decades happen." We are told by scholars and efficiency experts that the pace of technological change will only speed up over the next decade, that we'll experience more technological progress in the next 10 years than we have in the past century.

But even though this sounds daunting, it is not such a surprise. We still live – barely – in an age that celebrates progress for progress's sake and seems to regard it as a given. The interesting aspect of this change is that it is happening when there is profound change coming elsewhere in society, apart from the field of technology. There are four horsemen, so to speak, that will lead us into the future, a future which still seems mostly obscured and uncertain to our eyes:

-

Rapid technological change

-

Demographic collapse

-

Economic contraction as a result of debt

-

An imploding liberal order

Some hope that the trajectory of the first of these "horsemen," technological innovation, will somehow make up for the implosion of the other three. In this desperately hopeful vision, tech will make up for the lack of children, of workers in the future, provide new sources of income and prosperity, and more or less keep the liberal order – domestically in the west and globally as part of the so-called rules-based international system – in place. Maybe we can all be something like Japan. But such a comforting scenario seems far too rosy.

According to a 2024 survey of financial chiefs, "more than half (61%) of large firms plan to use AI within the next year" to automate work done by human employees. It is likely then that massive job disruption caused by the latest technological progress, something seen many times in the past, will happen sooner rather than later.

The coming economic contraction is not so much due to population collapse – the loss of workers and the loss of buyers – but because of massive debt that threatens many economies. Global public debt is expected to approach 100% of GDP in five years; it could be sooner, although the impact varies from country to country. The coming impact of tech on the world may be tremendous, but this has happened before in human history. There have certainly been debt bubbles before, and massive economic crises as recently as 2008. And countries have experienced population loss before, usually as a result of disaster and war, but we are in uncharted waters with technology advancing, debt exploding, populations declining, and the old ways of doing politics (and the politicians who created this collapsing world) discredited and exhausted, all happening globally at the same time.

It seems that everything that can be shaken will be shaken, and that "hollowed-out nations," those who built on sand and bet the most on a declining old order, could lose the most. If the United Kingdom seems a toxic symbol of a collapsing past, the United States seems to have just elected a president who understands the historical moment we are in and will try to radically adjust national policies accordingly. Whether Trump will have arrived in time to do the necessary triage is yet to be seen. The United States, despite a looming debt crisis, has some built in long-term advantages – plentiful domestic energy and food supplies – that its counterparts in Western Europe lack. But current economic and political models will be under tremendous stress almost everywhere.

Modern, "liberal" man, having shaken off or dissolved every bond through the illusory dogma of eternal progress and prosperity, will find himself alone, unarmed, and adrift. At best, he will "drink to his annihilation, twelve times quaffed," as Huxley's Brave New World puts it.

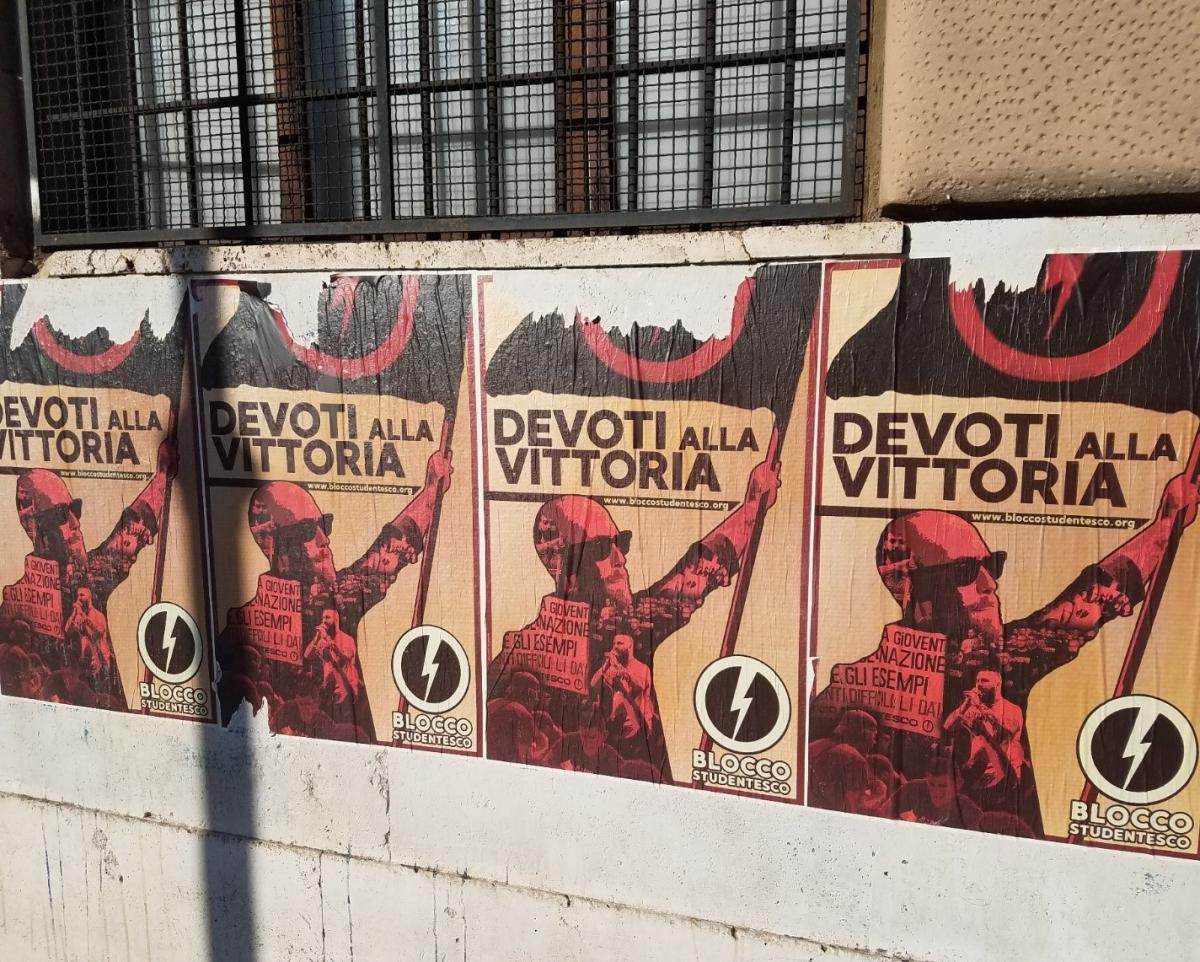

And who will lead? We not only have hollowed-out nations in the West, but hollow men, "men without chests," as C.S. Lewis called them, as the default leadership class – exhausted, bereft of vision, arrogant, their old tricks increasingly threadbare – clings to power. Their old insults don't work anymore – Trump was called a fascist – and won – and a British politician recently called Elon Musk a fascist too because he dared to speak about the UK's "Pakistani Grooming Gangs" scandal. Defamation and control of the legacy media (in order to prevent "disinformation") were the elite's remaining tools, but they seem to have lost their bite.

While coming events will shake us all, the future seems to belong to those who are grounded in... something elemental and lasting, whatever that is, as long as it is sincerely and powerfully felt and has stood the test of time. The Nation, the Umma, the Land, the Faith – all will be both in short supply and invaluable to those who keep them alive and close to their hearts. In that sense, someone like Syria's Ahmed Al-Sharaa, Romania's Călin Georgescu, or El Salvador's Nayib Bukele may look more like the future than whoever is the colorless, interchangeable bureaucrat of the day currently in charge of managing decline in Britain or Germany.

An "extreme" future, with citizens feeling trapped or lost, will likely lead to new levels of extreme political experimentation, the likes of which established Western states have not fully experienced for decades. Trump is actually the last of the moderates rather than the first of the extremists. Those may come later. Far-left, far-right, faith-based politics and populisms and reaction of every hue will eventually have their day. The old categories of right and left – and of what constitutes the center – will soon have lost their meaning.

*Alberto M. Fernandez is Vice President of MEMRI.