This year marks the 32nd anniversary of the assassination of Algerian president Mohamed Boudiaf. Even now, over 30 years later, the full truth about the assassination has still not come out.

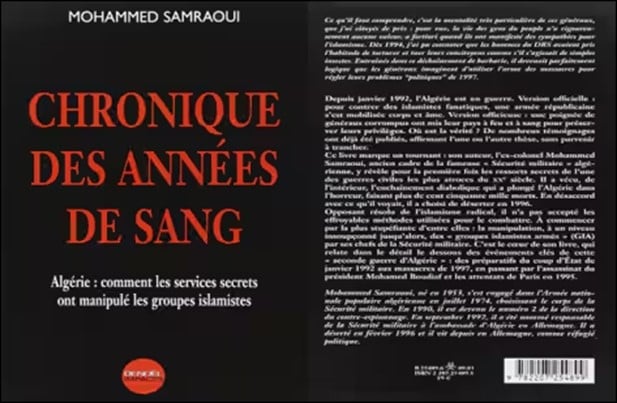

The book Chronique des années de sang (Chronicle of the Years of Blood, Éditions Denoël) by Mohammed Samraoui, a former colonel in the Algerian army who defected in 1996 and who has since been living in political asylum in Germany, is probably one of the best testimonies on the assassination of Boudiaf.[1]

Algerian president Mohamed Boudiaf

Samraoui: Boudiaf Was Not The "Puppet" The Generals Wanted

Following the landslide victory of the Islamic Salvation Front (FIS) in the first round of the December 1991 legislative elections, the army urged the regime to annul the second round. Thus, as reported by Samraoui, a war was launched by Algerian generals to safeguard the interests of a totalitarian regime.

Samraoui reported that in order to provide legal cover to the coup d'état that deposed President Chadli Bendjedid in January 1992 – a coup in which Samraoui himself took part – on January 12, the High Security Council (Haut Conseil de sécurité, HCS), an institution controlled by the army, declared that it was impossible to continue the electoral process. Two days later, the HCS decided that the state would be run for two years by a new body, the High Council of State (Haut Comité d'Etat, HCE), a "political fiction" created for the occasion and whose presidency was entrusted to Boudiaf. Boudiaf returned to Algeria on January 16; this date is no coincidence, as the second round was scheduled for the same date.

In fact, on January 10, 1992, Member of the High Council of State Ali Haroun (1927-), on the orders of the generals, went to Morocco to meet Boudiaf and to persuade him to return to Algeria. Boudiaf, a founding member of the National Liberation Front (FLN), had founded the Socialist Revolution Party (PRS) after Algeria's independence, but his opposition to Ben Bella, Algeria's first president, had forced him into exile in 1963. He spent 28 years in exile in France and then in Morocco, where he devoted himself to running his brick factory in the Moroccan city of Kénitra.

Yet Boudiaf, who was supposed to guarantee the historical legitimacy of power, was not the "puppet" the generals wanted. On June 29, 1992, on an official visit to Annaba unaccompanied by any senior regime figures, during a speech being broadcast live on television from the Maison de la Culture, President Mohamed Boudiaf was assassinated by an officer of his bodyguards,

Samraoui wrote in his book: "The assassin was an officer of the Special Intervention Group (Groupement d'Intervention Spéciale, GIS), a unit of the Department of Intelligence and Security (Département du Renseignement et de la Sécurité, DRS). He was Second Lieutenant (sous-lieutenant) Lembarek Boumaarafi, known as Abdelhak; he had joined the president's security team at the last minute, after having been accepted mere days earlier by Smaïn Lamari, head of the Counterintelligence Directorate (Direction du contre-espionnage, DCE, a branch of the Department of Intelligence and Security, DRS), at the Antar Center.

"With a personal mission order signed by Belouiza Hamou, head of the GIS, he [Boumaarafi] joined the rest of the group in Annaba on 27 June. After pulling the ring [pin] and throwing a grenade onto the stage to create a diversion, Boumaarafi emerged from behind the curtain and emptied the chamber into the president, the only victim. Taking advantage of the chaos and panic, the assassin got rid of his weapon before jumping a two-meter-high perimeter wall and taking refuge 400 meters away in a neighboring house, from where he telephoned the police and turned himself in."

Samraoui's book

Samraoui: Boumaarafi Was Never An FIS Sympathizer

Samraoui explained that not a single one of the 56 presidential guards had the presence of mind to react or neutralize the assassin: "The surprise effect does not explain everything. The bodyguards, although trained for this type of situation, may benefit from this excuse. Yet what about the guards, who were stationed outside of the building, at the exits, in the adjacent alleys, etc.? Why didn't they intervene? How can we believe that Boumaarafi was able to leave the Maison de la Culture and walk 400 without being disturbed, when in principle the entire surrounding area – what we call the security perimeter – was cordoned off by members of the security services? ... I do not believe that there is a single Algerian who is not convinced that the sponsors of this odious crime are indeed the military decision-makers."

The official version and the media initially attributed this assassination to a "DRS officer sympathetic to the FIS" before correcting themselves and concluding that it was an "isolated act." However, Samraoui specified that Second Lieutenant Lembarek Boumaarafi had never been an FIS sympathizer: "He is neither an Islamist, nor a mentally unbalanced person... He acted on command duty, obeying specific orders from the hierarchy, without his direct boss (Commander Hamou) being kept informed of the operation. It is worth noting that the DRS propaganda, echoed in the newspapers of the time, made Boumaarafi a 'son of a harki [Algerians who served as auxiliaries in the French Army during the Algerian War from 1954 to 1962].' This is absolutely false: a son of a harki can never make a career in the army, and even less so in the secret services...

"I knew Boumaarafi personally, as he was part of the platoon of Captain Abdelkader Khémène, who was an old acquaintance of mine (he had been seconded under my orders from 1980 to 1982, when he served as an officer in the 52nd battalion, then in the administration and support command battalion of the 50th Infantry Brigade: this former sergeant is today a colonel). I can therefore confirm that he [Boumaarafi] is a competent officer who was deliberately marginalized [from January to June 1992, he was confined to guard duty, with a minimum salary and harassed by 'fundamentalist groups,' which were manipulated by the secret services] in order to condition him and turn him into killer with no qualms."

Samraoui: The Role Of Smaïn Lamari

An interesting fact is that the weapon that Boumaarafi threw away after the assassination was never found. Hence, Samraoui wrote: "How to explain this mysterious disappearance? Boumaarafi had shot the president in the back, and, according to reliable sources, at least one bullet had perforated his thorax. Was there a second shooter? Why was an autopsy not carried out? And how to explain the shortcomings of the security arrangements? At least three agents of the Presidential Security Service (Service de sécurité présidentielle, SSP) directly involved in protecting the president were not at their posts at the time of the tragedy."

Furthermore, Samraoui wrote: "Corroborating sources (the secretary of the Main Operations Center, Centre principal des opérations, the driver Khaled, etc.), revealed that Smaïn Lamari had received Boumaarafi at the Antar Center the day before his departure on a mission to Annaba (i.e. two days before the assassination). What was the nature of the meeting? Could Boumaarafi refuse an order from Smaïn?"

About the role of Smaïn in the assassination of the president, Samraoui also stated: "During the Telemly operation [in the spring of 1992], which costed the life of Commander Amar Guettouchi (who was the head of the Antar Center, depending on the Counterintelligence Directorate, DCE) and of second lieutenant Tarek, two offensive grenades were given to me by Captain Abdelkader Khémène, of the GIS, at the end of the operation. I had placed them in a drawer in my office in Chateauneuf. However, on June 11, I left on a mission to Pakistan, only to return on June 27, two days before Mohamed Boudiaf's assassination. During my absence, the two grenades had disappeared; as I could not find any casualty reports, I deduced that they had been 'stolen' by someone in charge. And who could access my office if not my boss, Smaïn Lamari? In fact, in July 1993, Captain Ahmed Chaker, who was my deputy in Chateauneuf, confirmed to me that he had taken them.

"What caught my attention is that, in its report, the commission of inquiry into the assassination of the president claimed that the grenade, which Boumaarafi had detonated before shooting, had been kept by him since the Telemly operation – which is impossible, since he did not participate in it... With [Boumaarafi] not participating in any anti-terrorist operations, and considering that presidential security members are never equipped with grenades, Boumaarafi had no means of obtaining them. Someone... had therefore given him the grenade he used in Annaba. Taking into account all these elements, him the grenades recovered in my office, probably two days before the assassination."

Intimidation Of Members Of The National Commission Of Inquiry

Samraoui stated that many other facts confirm that "the assassination of the president was planned at the highest levels of power." For example, there were attempts to intimidate the members of the National Commission of enquiry, which had concluded that there had been "culpable negligence" and stated in its preliminary report dated July 26 1992: "The theory of an isolated action does not seem to us to be the most likely."

Samraoui explained: "On July 10, 1992, the lawyer Mohamed Ferhat, a member of the commission, was shot and wounded. On June 18, 1994, Yousef Fathallah, a notary and human rights activist who was also a member of the commission, was assassinated in his office in Algiers. His only fault was most probably his refusal to sign the investigation report, whose conclusions he did not agree with..... Fathallah wanted the sanctions to be limited not only to the members of the Special Intervention Group (Groupement d'Intervention Spéciale, GIS) and the Presidential Security Service (Service de sécurité présidentielle, SSP) who were present in Annaba on the day of the tragedy, but also to the main leaders of the security services. I also learned later that Fathallah was the only member of the commission of enquiry whom Boumaarafi trusted, to the point of sending him a personal letter shortly before his assassination."

Boudiaf Wanted A Real Change For Algeria

In his book, Samraoui also explained why Boudiaf was a problem for the military: "So Boudiaf's assassination was not the work of the Islamists. As I have already said, Boudiaf was killed because he hampered the plans of the military decision-makers – the same ones who had brought him back to Algeria – as he had begun to attack them.

"The president had just relieved General Nourredine Benkortbi – a close friend of General Larbi Belkheir [1938-2010] – of his duties as chief of protocol and was seriously considering cleaning up his entourage. In less than three months, he had dismissed three generals from the decision-making circle: Mohamed Lamari, commander of the ground forces; Hocine Benmaalem, head of the security affairs department of the presidency; and Noureddine Benkortbi, chief of protocol!

"These dismissals, and the spat with General Toufik (head of the Department of Intelligence and Security, DRS [from 1990 to 2015], whom Boudiaf had been planning to dismiss), the investigations into embezzlement that Boudiaf had launched, and the change of government that Boudiaf was planning and the political party he wanted to create (the RPN, National Patriotic Rally, which fell apart as soon as Boudiaf was assassinated) – all this this turned President Boudiaf into a man to be eliminated... The "Janvieristes" [i.e. the generals of the Algerian army], fearful of losing their privileges, therefore chose to go for the "strong method."

It is also worth noting that Boudiaf considered the Polisario Front to be a creation of the previous Algerian regimes and wanted to "distance himself definitively from the politics of agitation."

The Cynicism Of The Generals

To show the poor esteem in which the generals held Boudiaf, Samraoui quoted what Smaïn said by way of a funeral oration: "His only achievement was to die as a head of state." This cynicism was also shared by Gen. Khaled Nezzar, who told Samraoui in 1994: "Boudiaf was entitled to a state funeral, and that is already a lot for someone who sold tiles [referring to Boudiaf's brick factory in Kenitra]."

Samraoui stated that the assassination of the Algerian president would be the first of a long list of "liquidations" of renowned figures: "Some of the most prominent people that were killed were Kasdi Merbah, former head of government from 1988 to 1990 and former head of military security; Djillali Liabès, sociologist; Tahar Djaout, writer and journalist; Mohamed Boukhobza, sociologist; Djillali Belkhenchir, professor of pediatrics and vice-president and leader of the Algerian Committee against Torture; Said Mekbel, journalist and satirical columnist; Abdelhak Benhamouda, Algerian trade unionist..."

*Anna Mahjar-Barducci is a Senior Research Fellow at MEMRI.

[1] See MEMRI Daily Brief No. 644, Former Algerian Army Colonel On How Algeria's Secret Services Manipulated Islamist Groups During The 'Black Decade', By Anna Mahjar-Barducci, August 30, 2024.