Western policymakers' attention has been stuck to Ukraine since the very start of the Russian invasion, while the so-called "post-Soviet space" has received much less attention. This is understandable, even though this area may create difficult challenges in the future.

The Central Asian region, which once was a remote periphery of the Soviet Union, looks today like a kind of a Middle-Earth that lies between the two most significant challengers to the Free World, that is Russia and China, while experiencing influence also from Europe, Turkey, and the unstable broader Middle East. If one turns to Central Asia's recent history, it is possible to clearly distinguish three decisive periods, coming one after another since the demise of the Soviet Union.

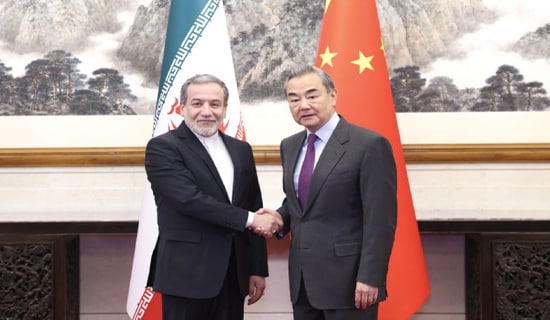

(Source: (Uz.usembassy.gov)

The "Multi-Vector Approach"

The independence of Kazakhstan, Uzbekistan, Kyrgyzstan, Tajikistan, and Turkmenistan, in late December 1991, originate from the decline and fall of the USSR, during which all these countries have been the most "disciplined" Soviet republics. Highly depending on financial subsidies arriving from Moscow, the leaders of all five entities favored reforms, but not the dissolution of the "eternal" union. However, after the Belavezha Accords on December 8, 1991, which formally dissolved the Soviet Union, the new Central Asia nations' initial steps were rather cautious as they tried to find their new destiny.

In fact, as early as in 1992, Nursultan Nazarbayev, the first president of Kazakhstan, which is the largest and most developed country in Central Asia, negotiated a deal with Russia, giving all the nuclear warheads stationed on Kazakh soil back to Moscow, and proclaimed a "multi-vector" foreign policy, pursuing equal cooperation with Russia, Europe, the United States, and China. This approach was later enshrined in Kazakhstan's foreign policy doctrine,[1] facilitating the region's development for decades.

During the 1990s and early 2000s, the "multi-vector approach" proved to be extremely effective. Russia has guaranteed the region's security via the Moscow-led Collective Security Treaty Organization (CSTO), established in May 1992, that included all the Central Asian countries except Turkmenistan. Moreover, in the region, Russia showed up as an effective peace broker, managing to end a bloody civil war in Tajikistan, which became the only serious conflict inside former Soviet borders that Russia has solved rather than provoked.[2] Russia, together with the local governments, also created a collective task force aimed at stopping Islamic terrorists from infiltrating from Afghanistan into the region and on fighting the drug trafficking and illicit trade.

On the other hand, Western powers became the main investors in the region's economies, being mostly interested in developing vast natural resources that remained largely unused during Soviet times. The best example is the massive investment into Kazakhstan's giant Tengiz oil field, made in the early 1990s, mostly by Chevron and ExxonMobil, which teamed up with Kazakhstan's state-owned KazMunayGas and controled a 75-percent stake in the joint venture.[3] In 20 years, more than $20 billion were invested in the project, which expanded in 2008 with another $37 billion of investments announced (since 1993, the project generated $176 billion in taxes and excise duties being channeled into Kazakhstan's budget).[4] More investment came later into Kazakhstan's oil and uranium industries, Kyrgyzstan's gold mines, Uzbekistan's metal-processing and chemical sectors, and other projects. Kazakhstan doubled its oil output between 1991 and 2003 and increased it by another 70 percent in the following 15 years.[5]

Moreover, China also evolved into a valuable partner to the region, increasing its trade almost fivefold between 1992 and 2000. Russia and Turkey competed in influencing the region culturally as Ankara set up dozens of cultural centers across Central Asia, while the Russian language retained its role despite the tremendous decrease of the share of ethnic Russians, Belarusians and Ukrainians in the first years after the Soviet collapse: between 1989 and 2010 it went down from 44.4 to 26.2 percent in Kazakhstan, from 24.3 to 6.9 percent in Kyrgyzstan, and from 8.5 to a mere 1.1 percent in Uzbekistan.[6]

The "Eurasian Integration"

Politically, the "multi-vector approach" fit well to the times: Russia was looking for a lasting alliance with the West and the entire world hoped China would evolve into a less authoritarian market economy. After the 9/11 Islamist terrorist attacks on the United States and the launch of the War on Terror, the U.S. and NATO developed their air force and logistical facilities in Uzbekistan and Kyrgyzstan, which Russia did not oppose at the time.

However, this idyllic era did not last too long, as Russia-Western relationships started to deteriorate after the 2003 Iraq War, the 2004 Orange revolution in Ukraine, and eastward expansion by both NATO and the EU. From this time, two confronting trends emerged. On the one hand, Russia embarked on a path toward "Eurasian integration," trying to bring Central Asia closer to itself, especially after all Putin's attempts to seduce Ukraine into establishing a closer cooperation failed. On the other hand, the Central Asian nations started to focus on identity politics as, for example, Kazakhstan, which rewrote the country's history textbooks and ordered the transition from Cyrillic to a Latin script.

Yet, the region retained strong economic and social connections to Russia, as millions of Uzbek, Tajik, and Kyrgyz guestworkers were employed by the Russian state-owned and commercial entities sending billions of dollars in remittances back to their home countries – constituting up to 39 percent of Tajikistan's and 23 percent of Kyrgyzstan's GDP already in early 2010s.[7] Hence, the Eurasian integration went on. The Eurasian Economic Union replaced the Eurasian Economic Community on January 1, 2015, facilitating the movement of goods and people across the borders and promising the creation of a common market by early 2020s. However, it was not a surprise that the Union has not become a success – all its members' economies, except that of Belarus, were highly dependent on the commodities sector so their bilateral trade did not have much space to grow and it increased by only 19 percent in eight years.[8]

Moreover, since Russia's GDP exceeded 80 percent of the Union's total, Moscow hesitated to introduce rules and regulations, which might enable the smaller members of the Union to impose common rules that Russia might not like. Another factor that limited Russia's influence was the change in power elites in Uzbekistan and Kazakhstan in 2016 and 2019 and these countries' subsequent turn onto a rapid modernization path, while Russia itself opted more for an economic autarky and social backwardness, both of which Russian President Vladimir Putin designated as "conservatism." Kremlin's war against Ukraine, waged at different levels of intensity since 2014, further contributed to Russia's economic unattractiveness.

Kremlin's Means Of Influencing Central Asian Leaders Are Exhausted

In recent years, a new trend appears to be dominant, reinforced both by China paying more attention to the region and Russia becoming totally obsessed by the "Ukrainian question." Since the early 2020s, the leadership in Beijing became finally disappointed by Russia's plans and promises to create a transcontinental transport corridor from East Asia to Western Europe and, as war turned Russia into a pariah state, China started its own program for building a multimodal transport corridor from Xinjian to Europe via Kyrgyzstan, Uzbekistan, Turkmenistan, Iran, and Turkey, which was detailed during the recent China-Central Asia summit in Xi'an in May, 2023.[9]

The Chinese leadership announced that it will provide Central Asian countries with a total of 26 billion yuan ($3.8 billion) in financing support and grants,[10] and gave a green-light to an impressive $27 billion package of commercial investment projects (bilateral trade with Beijing and Central Asia surpassed a record $70 billion in 2022),[11] unveiled more than a dozen new cooperation initiatives in the region, and introduced a visa-free regime with Kazakhstan – in other words, China made something Russia cannot match by any circumstances. Russia's accumulated FDIs in Central Asian countries are now lagging far behind China's, as Beijing firmly established itself as the region's largest trade partner.

What is crucial here is the fact that, while in the past, Russian officials voiced their concern over the growing Chinese influence in the region, now Moscow remains silent. I believe that the Kremlin now realizes that its means of influencing regional leaders are largely exhausted, as Russia became dependent on Kazakhstan and neighboring nations for importing the goods it needs from suppliers that are no longer doing business in Russia. Therefore, even though Russia still requires Central Asian leaders to express some "reverence" toward Mosco – for example, on May 9, all Central Asian leaders participated in the Victory Parade in Moscow[12] – the Kremlin does not oppose the rise of China's influence in "Middle-Earth," since it realizes that there is no alternative to it. Furthermore, China, as a "supposed" ally of Moscow, is preferable anyway to the Western powers that would want to expand cooperation with the region. The reader might remember how forcefully Russia pushed the U.S. military installations out of Uzbekistan and Kyrgyzstan in the 2000s and how silent it appears these days as China extends its Global Security Initiative on Central Asian nations.[13]

The Western Powers Seem Reluctant To Recognize Central Asia's Role

Observing the most recent trends that are evolving in the region, I would say that the old "multi-vector approach" has gone, as China is now on its way to securing a commanding role in the region's politics and economy. I would mention, however, that such a trend is not too inspiring for many locals, as a significant part of Kazakhstan and Kyrgyzstan citizens believe, both for "historical" and purely economic reasons, that China's rise is a challenge, if not a threat, to the region.

In 2016, revolts erupted in the towns of Atyrau, Aktobe, and Semey in Kazakhstan in response to rumors that China was allowed to lease around 1.7 million hectares of arable land in surrounding provinces. The Kazakh government rapidly changed its decision on the issue, introducing a moratorium on such deals that has been extended ever since.[14]

For decades, a large part of the local population, most of all urban dwellers, have valued quite highly the cooperation with the Western nations. Kazakhstan, for example, even opted for introducing the British legal system in its main free economic zone in order to attract more foreign investment.[15] The change that has started both in Uzbekistan and Kazakhstan has been hailed as an important shift toward "Europeanization," and not toward becoming a China-like dictatorship. The most recent legislative elections resulted in a unique six-party parliament in Kazakhstan, unseen in its history. But it seems that the Western powers greatly underestimate this Middle-Earth's importance for both the global strategic balance and for supplying Europe with much-needed natural resources – China already gets two thirds of its pipeline gas imports from Central Asian countries.[16]

The recent U.S. Secretary of State Anthony Blinken's visit to Astana was focused on Kazakhstan's compliance with anti-Russian sanctions,[17] which seems to be a minor issue when compared to the opportunities the region may provide for Western powers. It is worth noting that, during his visit, Blinken pledged a mere $25 million in funding to support economic growth in the entire region,[18] and the European delegation to the recent EU-Central Asia Economic Forum, which was led by Energy Commissioner Valdis Dombrovskis, did not include any head of states, making a strong contrast to recent high-level meetings in Moscow or to the China-Central Asia summit in Xi'an.[19] The European policymakers expressed some enthusiasm on the upcoming contacts with regional leaders – France's Emmanuel Macron is expected to visit Kazakhstan in autumn – but in general the Western powers seem reluctant to recognize the region's role in 21st-century geopolitical solitaire.

Conclusion

I think that the time has arrived to at least restore the balance once established by the introduction of the "multi-vector" policies. Both Europe and the U.S. possess significant levers allowing them to influence the Central Asian nations and their elites – but still do not react to the fact that in 2022, the region's foreign trade with China increased by $28.3 billion, compared to a $6.3 billion increase in its trade with Russia and a mere $1.1 billion increase in trade with the U.S. [20] The West has a vested interest in confronting the challenges posed by Islamic extremism far from its own borders, and all Central Asian countries would welcome more cooperation in the field.

The Western countries possess the world-class technologies to be shared with the regional companies in traditional and green energy, agriculture, manufacturing, the financial sphere, and all other industries. It is in the West's interest to have Kazakhstan's modernization be Western-inspired rather than a Chinese-orchestrated.

Last but not least, securing the region's independence from both China and Russia looks like an important strategic goal enabling liberal and democratic trends to survive and grow stronger. The future trajectory of Kazakhstan, as the largest Central Asian state, is by far the most important here. The sooner the European and American leaders realize the real value of the region and the opportunities it provides in countering the West's most powerful challengers, the stronger the international liberal order will be in the coming decades.

*Dr. Vladislav Inozemtsev is the MEMRI Russian Media Studies Project Special Advisor, and Founder and Director of the Moscow-based Center for Post-Industrial Studies.

[1] Adilet.zan.kz/rus/docs/U2000000280#z9, March 6, 2020.

[2] Ia-centr.ru/experts/iats-mgu/vklad-rossii-v-uregulirovanie-grazhdanskoy-voyny-v-tadzhikistane-byl-reshayushchim/

[3] Ulysmedia.kz/news/15672-kakuiu-vygodu-poluchil-kazakhstan-za-30-let-partnerstva-s-kompaniei-shevron/, May 5, 2023.

[4] Trend.az/business/energy/2135237.html, April 3, 2013; Kazpravda.kz/n/amerikantsy-vlozhat-pochti-37-mlrd-v-uvelichenie-neftedobychi-na-tengize/, July 6, 2016; Tengizchevroil.com/docs/default-source/tcodocuments/facts-and-figures/ru/2022/tco-fact-sheet-4q-2022_final_r.pdf?sfvrsn=f8e1c55c_2, 2022

[5] Energyinst.org/__data/assets/excel_doc/0007/1055545/EI-stats-review-all-data.xlsx

[6] Mk.ru/politics/2013/04/21/844895-rossii-pora-otdelitsya-ot-byivshego-sssr.html, April 21, 2013.

[7] Rg.ru/2012/11/22/perevodi-site.html, November 22, 2012.

[8] Eurasiancommission.org/ru/act/integr_i_makroec/dep_stat/tradestat/time_series/Documents/Time Series Internal Trade/Internal trade_Export_data by year.xls

[9] Reuters.com/world/asia-pacific/chinas-xi-calls-stable-secure-central-asia-2023-05-19/, May 19, 2023.

[10] Reuters.com/world/asia-pacific/chinas-xi-calls-stable-secure-central-asia-2023-05-19/, May 19, 2023.

[11] Reuters.com/world/asia-pacific/chinas-xi-calls-stable-secure-central-asia-2023-05-19/, May 19, 2023.

[12] Ria.ru/20230508/parad-1870519381.html, May 8, 2023.

[13] Fmprc.gov.cn/mfa_eng/wjbxw/202302/t20230221_11028348.html, February 21, 2023.

[14] Bbc.com/russian/international/2016/04/160429_kazakhstan_land_rent_protests, April 29, 2016; Ru.sputnik.kz/20161209/parlament-rk-prodlil-moratorij-na-rezonansnye-normy-zemelnogo-kodeksa-1181014.html, December 9, 2016.

[15] Informburo.kz/stati/zachem-kazahstanu-angliyskaya-pravovaya-sistema-eksperiment-fincentra-astana-.html, April 28, 2018.

[16] Scmp.com/news/china/diplomacy/article/3220788/how-energy-powering-chinas-relationships-central-asia, May 17, 2023.

[17] Bloomberg.com/news/articles/2023-02-28/us-closely-eyes-sanctions-evasion-in-central-asia-blinken-says, February 28, 2023.

[18] Usip.org/publications/2023/05/china-looks-fill-void-central-asia, May 25, 2023.

[19] Eeas.europa.eu/delegations/kyrgyz-republic/second-european-union-%E2%80%93-central-asia-economic-forum-was-held-almaty_en, May 22, 2023.

[20] Rbc.ru/politics/21/05/2023/64677fc49a79472fac8cab00, May 21, 2023.