As Israel and some of the Gulf countries enter a new era of diplomatic and business relations, it should be realized that Jews have had a long history in that part of the Arab world. Jews were present in the Arabian Peninsula long before the birth of Islam. Their presence came to an end under the second Islamic Calif Omar (634-644), who expelled them, in keeping with a hadith from Muwatta Malik, who taught at the mosque of the Prophet Muhammad.[1] According to the hadith, Muhammad said "La yajtami' dinan fi jazirat al-Arab" – that is, "two religions shall not coexist in the Arabian Peninsula."[2] Additionally, in an historic change of attitude, the Imam of the Grand Mosque of Mecca, Islam's holiest shrine, referred in a recent Friday sermon to the friendly relations between Muhammad and the Jews.[3]

Unlike the large Jewish communities in Iraq, Egypt, Yemen, and North Africa, the number of Jews in the Gulf countries never exceeded a few hundred in any one country. This report will focus on the Jewish presence in some of the Gulf countries from the 19th century to the present, based primarily on a well-documented book by Kuwaiti scholar Yusuf Ali Al-Mutairi titled al-yahud fi al-khaleej ("Jews in the Gulf"),[4] as well as some additional material that has recently become available.

The Origins Of The Jews In The Gulf

Most of the Jews who settled in the Gulf countries, primarily in Kuwait and Bahrain, were of Iraqi origin, and many of them were seeking either to escape military conscription under the Ottoman Empire or to explore economic opportunities. Of these Jews, only a few have remained, likely only in Bahrain where the Jewish population numbers around 70. A member of that community, Huda Nonoo, was her country's ambassador to the U.S. from 2008 to 2013 – making her the first ambassador of the Jewish faith to represent an Arab country.

According to Al-Mutairi, Jews held important positions in Ahsaa (currently in eastern Saudi Arabia), notably the post of treasurer of the Ottoman Empire, which ruled the area through WWI. The post was held by three successive Jews – Yacoub Efendi, 1878-1879; Daoud bin Shintob ("Shintob" being an Arabicization of the Hebrew "Shemtov"), 1879-1894; and Haroun Efendi, 1895-96.[5] During their tenure, many of the entries in the financial books were in Hebrew (most likely in Arabic transliterated in Rashi script, which was commonly used by old-generation Iraqi Jews). Al-Mutairi suggested that keeping the financial records in Hebrew may have been aimed at preventing an audit of the accounts, possibly to protect their Ottoman superiors. But perhaps the most significant post held by a Jew was that of Director of Customs for the whole province – a highly desirable position sought after by many both inside and outside Ahsaa because of the potential it offered for illicit income.[6]

The Jewish Cemetery In Ahsaa

Not long ago, a Saudi friend of the author of this article mentioned the existence of a Jewish cemetery in Ahsaa. According to this information, the land on which the cemetery was located is largely deserted, and no one has claimed it, although locals continue to refer to it as maqbarat al-yehud – "the Jewish cemetery." Given that only a few Jews lived and died in the area, the cemetery itself could not have been large.

The Jews In Kuwait

The Jews in Kuwait numbered between 100 and 200; they had their own synagogue, called a kanisah. A British diplomat, John Gordon Lorimer, hinted at tensions with the local authorities "chiefly for the distillation of spirituous liquors which some of the Mohammadan [Muslim] population consume secretly in dread of the Sheikh."[7]

A Jewish Official In Muscat, Oman

Jews had been living in Muscat since at least 1625. In 1673, according to one traveler, a synagogue was being built, implying permanence. British officer James Wellsted also noted the existence of a Jewish community when he visited in the 1830s.

A fascinating discovery was made not long ago in the British Library: a letter written in 1859 by a British naval officer in the Gulf, Griffith Jenkins, to a subordinate in Muscat named Hezkel ben Yosef, to whom Jenkins refers in the letter as "Agent of British Monarchy." In the letter, Jenkins refers obliquely to the Imam who held sway in Oman's interior and concludes by asking Hezkel to explain the matter in private – and then, interestingly, had the letter translated into Hebrew. It reads, in part:

'"From commander Griffith Jenkins

"To Mr. [adon in Hebrew] Hezkel ben Yosef

"Agent of British Monarchy in the City of Muscat

"Regarding the matter that you informed me [about]..."

The unusual step of translating into Hebrew a letter from a British naval officer to his subordinate was interpreted by the British Library as a form of a code language to prevent unauthorized persons from learning its content.

Image copyright British Library

Notable Post-Rapprochement Events

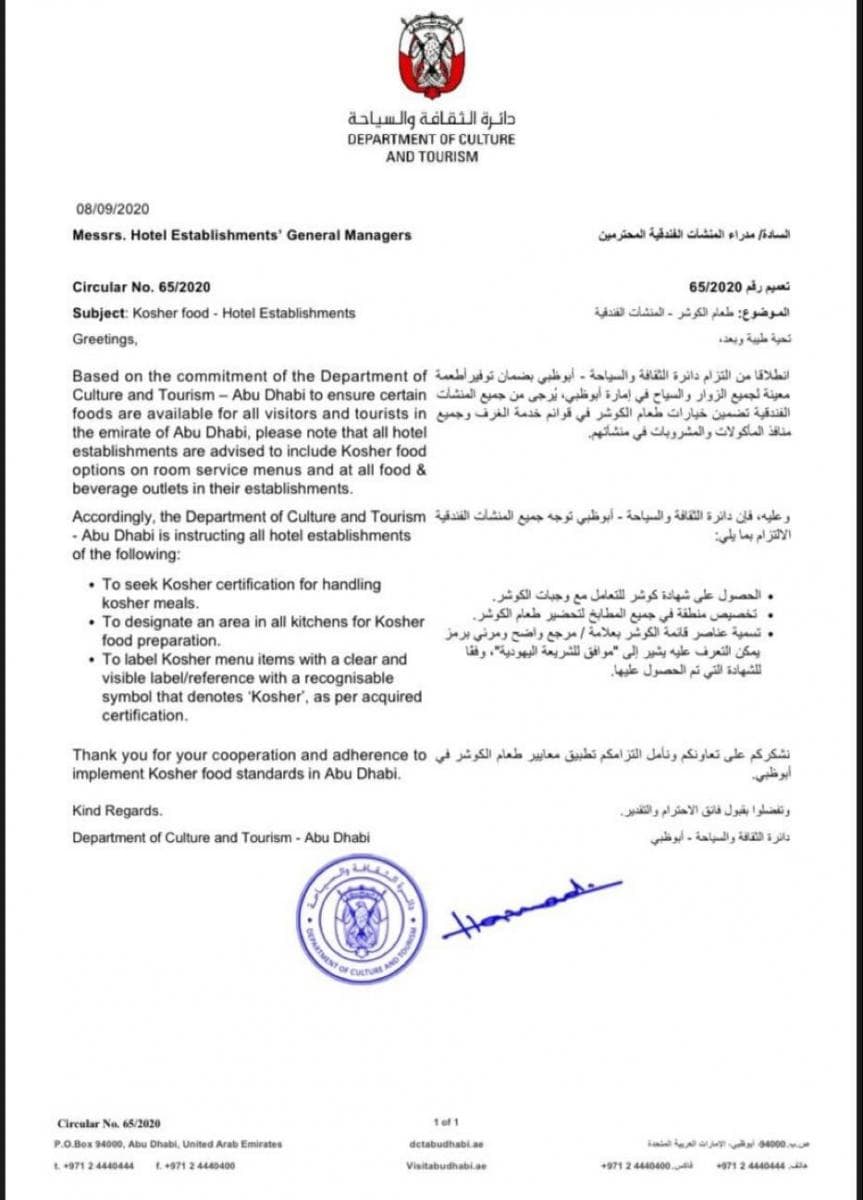

Since the signing of the peace agreement between Israel and UAE and Bahrain, there appears to be rapid progress towards an active peace. The letter below, concerning the rules of kashrut (keeping kosher), issued by the UAE Department of Culture and Tourism, may be the most significant sign of this.

Also noteworthy are statements by UAE Minister of State Shamaa Al-Mazrui regarding the similarities between Islam and Judaism, in which she first referred to herself as "a new student of the Jewish tradition and wisdom," and then referred to "the wisdom of Shabbat [the Jewish Sabbath]."[8]

*Dr. Nimrod Raphaeli is MEMRI Senior Analyst (Emeritus). Dr. Raphaeli was born in Basra, Iraq and worked for the World Bank from 1969 through 1997.

[1] Freekitab.com/muwatta-malik-english November 9, 2014.

[2] "Yahya related to me from Malik from Ibn Shihab that the Messenger of Allah, may Allah bless him and grant him peace, said, 'Two deens [religions] shall not co-exist in the Arabian Peninsula.' Malik said that Ibn Shihab said, ''Umar ibn al-Khattab searched for information about that until he was absolutely convinced that the Messenger of Allah, may Allah bless him and grant him peace, had said, 'Two deens shall not co-exist in the Arabian Peninsula,' and he therefore expelled the Jews from Khaybar.' Malik said, ''Umar ibn al-Khattab expelled the jews from Najran (a jewish settlement in the Yemen) and Fadak (a Jewish settlement thirty miles from Madina). When the Jews of Khaybar left, they did not take any fruit or land. The Jews of Fadak took half the fruit and half the land, because the Messenger of Allah, may Allah bless him and grant him peace, had made a settlement with them for that. So Umar entrusted to them the value in gold, silver, camels, ropes and saddle bags of half the fruit and half the land, and handed the value over to them and expelled them." Sunnah.com/urn/530180.

[3] See MEMRI TV Clip No. 8259, Friday Sermon at Mecca Grand Mosque by Imam Abdul-Rahman Al-Sudais: When the Method of Human Dialogue is Ignored, the Language of Violence, Hatred Prevails, September 4, 2020.

[4] Yusuf Ali Al-Mutairi, al-yahud fi al-Khaleej, Beirut, Lebanon, Dar Mudarak, 2011.

[5] "Efendi" is an honorary title used during the Ottoman Empire for junior government employees.

[6] Al-Mutairi, pp. 117-119.

[7] Bbc.com/news/blogs-magazine-monitor-30447043, December 13, 2014.

[8] The Times of Israel, September 29, 2020.