The following is an Inquiry and Analysis report by Tufail Ahmad, MEMRI Senior Fellow for the MEMRI Islamism and Counter-Radicalization Initiative. It was first published on November 19, 2019.

May 8, 2003: Qatar's emir Hamad bin Khalifa Aal Thani meets with George Bush in Washington

Introduction

This report examines Qatar's relationships with jihadi organizations. Right through the 1980s, Afghan mujahideen – backed by the U.S., Pakistan, Saudi Arabia, and Arab donors – fought against the Soviet troops from their hideouts in the mountainous terrains of Afghanistan. Since the 9/11 attacks on New York, the Pentagon, and other American targets, the Islamic Emirate of Afghanistan (the Afghan Taliban, especially its Haqqani Network) has been fighting and killing American and NATO soldiers from its shelters in Afghanistan and in Pakistani cities such as Abbottabad, Rawalpindi, Karachi, and Quetta.[1]

While this situation has not changed, a new dimension has been added since 2013: As part of a highly ingenious plot, which the world is yet to realize, the Afghan Taliban leaders' hideouts have moved to the safe haven of Doha, the capital of Qatar, from where the senior-most Taliban commanders plot, direct, and execute terror attacks on U.S. and NATO troops in Afghanistan. These jihadi leaders execute such anti-U.S. activities while dining with American officials in Qatar's luxurious hotels in the name of peace talks.

While American taxpayers bear the cost of the meals that U.S. officials have with the Taliban commanders in Qatar, it is disturbing to learn that three top commanders of the Haqqani Network – Anas Haqqani, Hafiz Rashid, and Haji Mali Khan – may soon settle in Doha, Qatar. Under a U.S. deal with the Taliban, the Afghan government reluctantly agreed to free the three terrorists in exchange for two Western professors of the American University of Afghanistan.[2] The attempt to move the Haqqani Network's commanders to Doha is perfectly in tune with Qatar's long-standing relationship with jihadi commanders, as this report will review.

The Trilateral Relationship Between Qatar, Pakistan, And The Taliban

A November 13, 2019 report in Roznama Ummat, a pro-Taliban Urdu-language daily, noted that the three Haqqani Network commanders will "be taken to Qatar within a week."[3] The Haqqani Network, founded by late jihadi commander Jalaluddin Haqqani, and now run by his son Sirajuddin Haqqani, is a highly effective terror organization within the Afghan Taliban. On September 22, 2011, Adm. Mike Mullen, the then chairman of the Joint Chiefs of Staff, testified before the Senate Armed Services Committee that the Haqqani Network carried out a truck bombing at a NATO post and another attack on the U.S. Embassy in Kabul earlier that month.[4]

Two of the three terrorists being freed are related to Sirajuddin Haqqani: Anas Haqqani is Sirajuddin's brother, and Hafiz Rasheed is their maternal uncle. Of the third terrorist being freed, Roznama Ummat noted: "[Haji Mali Khan] has played an important role in the reorganization of the Haqqani Network and training of its commanders."[5]

Qatar and Pakistan are working in tandem to move the Taliban leaders to Doha. This suits Pakistan, which has been under scrutiny by the international community for supporting the Taliban. Further, not only do these commanders work freely from Qatar, but they also help Pakistan escape international scrutiny for its support to them. The Haqqani Network is a terror behemoth with up to 20,000 members.[6]

Three Haqqani Network terrorists freed for two western academics

In his 2011 testimony, Mullen clearly said that the Haqqani Network executed the terror attacks with the aid of the Pakistani military's Inter-Services Intelligence (ISI), stating: "The Haqqani Network acts as a veritable arm of Pakistan's Inter-Services Intelligence agency" and "with ISI support, Haqqani operatives planned and conducted that truck bomb attack, as well as the assault on our [American] embassy."[7] America's top military general added: "We also have credible evidence that they were behind the June 28th attack against the Intercontinental Hotel in Kabul and a host of other smaller but effective operations."[8]

In the years after 9/11, Qatar emerged as a preferred host for jihadi groups and their commanders. In 2016, a journalist reported: "In one western district [of Doha], near the campuses hosting branches of American universities, Taliban officials and their families can be found window-shopping in the cavernous malls."[9] The report noted: "Officials from Hamas, a Palestinian militant group, work from a luxury villa near the British Embassy, and recently held a news conference in a ballroom at the pyramid-shape Sheraton hotel."[10]

Qatar's critics say: "Doha, rather than the benign meeting ground described by Qataris, is a city where terrorism is bankrolled, not battled against."[11] Qatar is also host to the radical Egyptian cleric Sheikh Yusuf Al-Qaradawi, who radicalizes Muslims by issuing statements such as: "We have the 'children bomb,' and these human bombs must continue until liberation."[12]

Qatari Emir's Role In Protecting "The Principal Architect Of The 9/11 Attacks"

In 1996, Qatari emir Hamad bin Khalifa Aal Thani helped Khalid Sheikh Mohammed escape.

Qatar also has a long-standing relationship with not only the Taliban and Haqqani Network but also with Al-Qaeda commanders and Pakistani jihadis such as Khalid Sheikh Mohammed. According to Richard A. Clarke, who served as National Coordinator for Security and Counter-Terrorism under presidents Bill Clinton and George W. Bush, Qatar was instrumental in foiling the arrest of Khalid Sheikh Muhammad (KSM) – the Pakistani terrorist described in The 9/11 Commission Report as "the principal architect of the 9/11 attacks" on American cities.[13]

The 9/11 Commission Report observed: "In 1992, KSM spent some time fighting alongside the mujahideen in Bosnia and supporting that effort with financial donations. After returning briefly to Pakistan, he moved his family to Qatar at the suggestion of the former minister of Islamic affairs of Qatar, Sheikh Abdallah bin Khalid bin Hamad Aal Thani. KSM took a position in Qatar as project engineer with the Qatari Ministry of Electricity and Water. Although he engaged in extensive international travel during his tenure at the ministry – much of it in furtherance of terrorist activity – KSM would hold his position there until early 1996, when he fled to Pakistan to avoid capture by U.S. authorities."[14]

However, it was the Qatari government that enabled KSM to flee. According to The 9/11 Commission Report, after an indictment against KSM was obtained from a U.S. court in January 1996, "an official in the government of Qatar" warned KSM about it and he successfully "evaded capture (and stayed at large to play a central part in the 9/11 attacks)."[15] It was also from Qatar that KSM wired money to Mohammed Salameh, a co-conspirator of Ramzi Yousef, who had been involved in several other terror plots and was convicted in the U.S. for his role in the 1993 World Trade Center bombing.[16]

Clarke, who chaired the multi-agency Counter-Terrorism Security Group (CSG), noted that 9/11 attacks could have been prevented if KSM's arrest was not foiled by Qatar. He wrote: "We could not trust the Qatar government sufficiently for us to do what otherwise would have been obvious: ask the local security service to arrest him and hand him over. The Qataris had a history of terrorist sympathies and one cabinet member in particular, a member of the royal family, seemed to have ties to groups like Al-Qaeda and appeared to have sponsored KSM."[17]

However, a decision was taken to talk to the Qatari government to arrest KSM. "Within hours of the U.S. ambassador's meeting with the Emir [of Qatar to seek the arrest], KSM had gone to ground. In tiny Doha, no one was able to find him. Later, the Qataris told us that they believe he had left the country. They never told us how," Clarke noted.[18] In 1996, Hamad bin Khalifa Aal Thani was the emir of Qatar, succeeded later by his son Tamim bin Hamad Aal Thani.

Qatar's Long-Standing Relationship With The Afghan Taliban

October 31, 2019: Afghan Taliban leader Mullah Baradar Akhund hands over certificates to students at a graduation ceremony in Doha

In the years after 9/11 terror attacks, several Taliban commanders moved to Qatar, which was seen by them as a hospitable refuge for jihadis. Taliban leaders like Mullah Abdul Salam Zaif, a former Guantanamo Bay prisoner and the Taliban's ambassador to Pakistan in pre-9/11 years, moved to Doha, whereas some Taliban members arrived as Afghan laborers and businessmen to work in Qatar.[19] Mullah Abdul Aziz, a former first secretary of the Taliban government's pre-9/11 embassy in the UAE, moved to Doha, ostensibly as a businessman.[20] Tayyab Agha, a former official of the Taliban leadership office in Kabul, emerged in Qatar as the Taliban's lead negotiator, though he resigned in 2015, over internal differences, as the head of the Taliban's Doha-based Political Office.[21]

Qatar's hospitality of jihadi commanders was a result of its state policy pursued by the Aal Thani royal family. Around 2010, Sheikh Hamad bin Khalifa Aal Thani, the emir of Qatar till 2013 and father of the current emir, Tamim bin Hamad Aa Thani, was being billed as "the Arab Henry Kissinger."[22] The United States shut its eyes to Qatar's support for the terror organizations operating in and outside the Middle East, especially in Bosnia.[23] According to one report, even before 9/11, Qatar "did have cordial relations with the [Taliban] militants" during 1996-2001 when the Taliban ruled Afghanistan from Kabul.[24]

Qatar's deep influence among the Taliban was also evident in the release of Canadian citizen Colin Rutherford. For five years to 2016, Rutherford was held captive by the Afghan Taliban. When the militants freed him in 2016, Qatar's envoy to Ottawa Fahad Mohamed Kafoud noted that "instructions" to help free Rutherford came from Qatar's emir, adding: "We received direct instruction from our government and from His Highness the Emir to facilitate and to do our best."[25] According to the Qatari government's website, Canadian Prime Minister Justin Trudeau made a personal telephone call to Qatar's Emir Tamim bin Hamad Aal Thani "in which he expressed deep gratitude and thanks to HH the Emir for the efforts made by the State of Qatar."[26]

Arrival In Qatar Of The Five Taliban Commanders From Guantanamo Bay

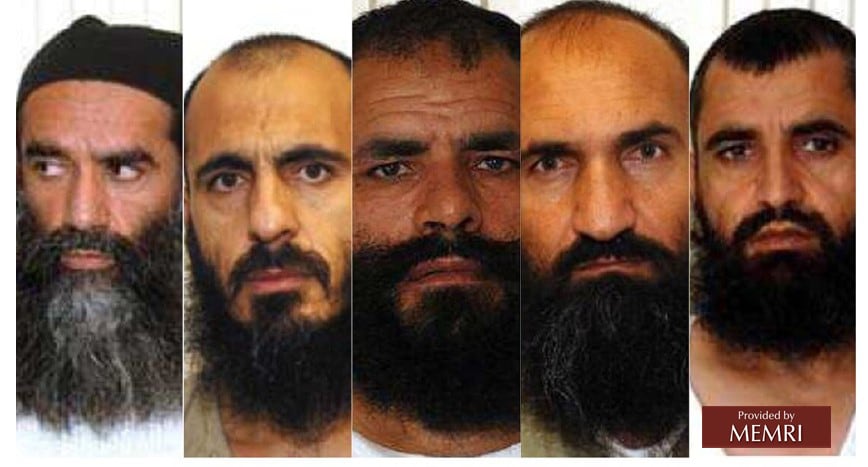

Five Taliban leaders released from Guantanamo Bay detention center, from left to right: Mullah Norullah Nori, Mohammed Nabi Omari, Mohammed Fazl, Khairullah Khairkhwa, and Abdul Haq Wasiq.

In 2014, the United States Treasury Department's Undersecretary for Terrorism and Financial Intelligence David Cohen said: "Distressingly, Iran is not the only state that provides financial support for terrorist organizations... Qatar, a longtime U.S. ally, has for many years openly financed Hamas, a group that continues to undermine regional stability. Press reports indicate that the Qatari government is also supporting extremist groups operating in Syria."[27] However, driven by a strong desire for talks with the Taliban, the Obama White House overlooked the Qatari government's support for terrorist organizations.

In March 2009, then U.S. President Barack Obama – motivated by "the success of the U.S. strategy of bringing some Sunni fighters in Iraq to the negotiating table" – said that "there may be some comparable opportunities in Afghanistan and the Pakistani region."[28] In fact, by then he had decided to talk to the Taliban. Speaking on International Women's Day in 2009, then Afghan President Hamid Karzai noted: "Yesterday [March 7], Mr. Obama accepted and approved the path of peace and talks with those Afghan Taliban who he called moderates."[29]

In and around 2010, the Taliban leaders had begun arriving "secretly" in Qatar as part of efforts to engage with American officials.[30] In 2013, a report noted that "more than 20 relatively high-ranking Taliban members" lived in Qatar.[31] It was estimated in 2018 that "about three dozen Taliban leaders" lived in Doha with their families.[32]

While President Obama initiated the process of talks with the Taliban in 2009, another incident happened in Afghanistan that year. Sgt. Bowe Bergdahl of the U.S. Army walked away from his unit in Afghanistan and was held by the Taliban for several years. The initial series of contacts between the U.S. and the Afghan Taliban involved the freedom of Sgt. Bergdahl in exchange for five top Taliban leaders being freed from the Guantanamo Bay detention center in 2014. Following their release these five leaders went to Qatar. According to a report, "Qatar played a role in brokering" Sgt. Bergdahl's release.[33]

The five Taliban prisoners who joined the Taliban's Political Office in Doha are: Mohammed Fazl, the former Taliban army chief; Khairullah Khairkhwa, a former governor of Herat province; Abdul Haq Wasiq, the Taliban's deputy intelligence minister; Mullah Norullah Nori, a close confidant of the late Taliban leader Mullah Mohammad Omar; and Mohammad Nabi Omari, a Taliban communications officer.[34]

In 2010, Mullah Abdul Ghani Baradar Akhund, a top Taliban leader, was arrested in a joint U.S.-Pakistani intelligence operation and was released in 2018. Following his release he went to Doha where he replaced Sher Mohammad Abbas Stanekzai as the head of the Political Office in early 2019.[35] Mullah Baradar Akhund – who has led delegations to Indonesia, Uzbekistan and Pakistan in 2019 – also holds the post of the Islamic Emirate's Deputy Emir for Political Affairs. Mullah Baradar Akhund, a key terrorist commander until 2018, now acts from his base in Qatar as the head of the state of Afghanistan, rejecting the existence of the elected Afghan government.

Qatar's Violation Of Afghanistan's Conditions For Hosting Taliban Leaders

In 2013, as the United States was pressing for a dialogue with the Taliban to end the war in Afghanistan, then Afghan President Hamid Karzai reluctantly agreed with the U.S. to allow for the Islamic Emirate's Political Office to be established in Doha. However, Karzai laid down some conditions: "[The Political Office] would maintain a low profile and work only as a venue for peace talks... [And it would not] be used for other activities, such as the expansion of Taliban ties with the rest of the world, recruitment or fundraising."[36] All of these conditions have been repeatedly violated by the Taliban on the watch of the Qatari leadership.

The Political Office opened on June 8, 2013, in Doha. The first condition that it would maintain "a low profile" was violated on the first day. It came as a shock to Afghans and the Afghan government that "an opening ceremony" was organized for this purpose while the Taliban were "yet to renounce" their "known ties to Al-Qaeda."[37] A former Afghan official noted that organizing such a ceremony for the jihadi terror group was "contrary to the careful policy agreements and diplomatic exchanges which had been worked in details between President Karzai, the United States and other relevant parties, including efforts by the Qatari government," yet the main parties, being the U.S. and the host Qatar, allowed for it.[38]

July 9, 2019: Qatar's current emir Tamim bin Hamad Aal Thani meets with U.S. President Donald Trump

Subsequently, the Political Office did become the venue for peace talks. However, another of the three conditions set by President Karzai was violated routinely as the Taliban began using it for diplomatic outreach with other nations for holding bilateral talks, thereby undermining the role of the Afghan government in international relations. On the watch of the U.S. and Qatar, the elected Afghan government was undermined regularly and repeatedly.

From the Doha-based Political Office, the Taliban commanders began acting as the sole government of Afghanistan on the international stage. Since 2013, the Taliban have sent delegations to Japan, Iran, Norway, Russia, China, Germany, Uzbekistan, Indonesia, and formally to Pakistan.[39] Their objective was to achieve international legitimacy as the sole representative of the state of Afghanistan.

At least one of the five Guantanamo Bay detainees freed by the U.S. had "contact with members of the Al-Qaeda-affiliated Haqqani Network during the past year [in 2015] while in Qatar," whereas "the U.N. acknowledges their sanctions have been circumvented" by the Taliban leaders based in the Doha office.[40] These are not the only violations by the Doha-based Taliban leaders of the conditions set by President Karzai.

In November 2019, it emerged that the Taliban run religious schools in Qatar: Abdullah bin Abbas Dar-ul-Huffaz and Abdullah bin Masood Dar-ul-Huffaz. Evidently, a terrorist group, given an office to hold talks with the U.S., is being allowed by the Qatari government and the U.S. to spread its tentacles. On October 31, 2019, the Taliban also organized a graduation ceremony for the students which was attended, according to a Taliban website and a video report, by 20 people, including the Taliban and other Afghans based in Qatar.[41]

Some very young students sitting alongside the Taliban leaders in the audience at a graduation ceremony in Doha on October 31, 2019

In recent years, questions have been raised about Qatar's role in facilitating and legitimizing the activities of the Afghan Taliban. In 2018, Mutlaq bin Majed Al-Qahtani – Qatar's special envoy for counterterrorism and conflict resolution – was asked specifically about this and, while arguing that it was the U.S. that wanted Qatar to host the Taliban's Political Office, noted: There was "no military solution" to the Afghan situation.[42]

It is unfortunate that a terrorist organization, which was operating more like a guerrilla force from its hideouts in the mountainous terrain of Afghanistan, has moved to the safe haven of Doha. In September 2013, a former Afghan official warned that in addition to deriving legitimacy through the Political Office, the Taliban "hope to kill their way back to power in Afghanistan and help create the same state which gave rise to a safe home to Al-Qaeda."[43] This prescient remark appears more real than ever as the world moves into the year 2020.

* Tufail Ahmad is Senior Fellow for the MEMRI Islamism and Counter-Radicalization Initiative

[1] While Quetta has served as the operational headquarters of the Afghan Taliban, it was in Abbottabad that U.S. special forces found and killed Al-Qaeda leader Osama bin Laden.

[2] The two professors are U.S. national Kevin King and Timothy Weeks of Australia, whom the Haqqani Network abducted in Kabul in August 2016. It should be noted that King and Weeks were freed on November 19, 2019.

[3] Roznama Ummat (Pakistan), November 13, 2019.

[4] The New York Times (U.S.), September 23, 2011.

[5] Roznama Ummat (Pakistan), November 13, 2019.

[6] MEMRI JTTM report, Pakistani Daily: 'Haqqani Network: Another Behemoth In The Making'; It has 15,000 – 20,000 Active Sympathizers, February 14, 2011.

[7] The New York Times (U.S.), September 23, 2011.

[8] The New York Times (U.S.), September 23, 2011.

[9] Nytimes.com (U.S.), July 16, 2017.

[10] Nytimes.com (U.S.), July 16, 2017.

[11] Nytimes.com (U.S.), July 16, 2017.

[12] Nytimes.com (U.S.), July 16, 2017.

[13] The 9/11 Commission Report. For further discussion of Qatar's role involving the Afghanistan-Pakistan jihadis, see MEMRI Daily Brief The US-Taliban Negotiations: A Deadly Qatari Trap, by Yigal Carmon, September 1, 2019.

[14] The 9/11 Commission Report.

[15] The 9/11 Commission Report.

[16] The 9/11 Commission Report.

[17] Nydailynews.com (U.S.), July 6, 2017.

[18] Nydailynews.com (U.S.), July 6, 2017.

[19] Bbc.com (UK), June 22, 2013.

[20] Thedailybeast.com (U.S.), April 24, 2017.

[21] Arabnews.com (Saudi Arabia), August 4, 2015.

[22] Bbc.com (UK), June 22, 2013.

[23] It appears the Qatari royal family did know of Khalid Sheikh Mohammed, the mastermind of 9/11 attacks, since his days in the Bosnian jihad.

[24] Bbc.com (UK), June 22, 2013.

[25] Nationalpost.com (Canada), January 11, 2016.

[26] Mofa.gov.qa (Qatar), January 12, 2016.

[27] Cnsnews.com (U.S.), June 10, 2014.

[28] Aljazeera.com (Qatar), March 9, 2009.

[29] Aljazeera.com (Qatar), March 9, 2009.

[30] Bbc.com (UK), June 22, 2013.

[31] Bbc.com (UK), June 22, 2013.

[32] Nytimes.com (U.S.), October 31, 2018.

[33] Nationalpost.com (Canada), January 11, 2016.

[34] Militarytimes.com (U.S.), October 30, 2018.

[35] MEMRI JTTM report Afghan Taliban Appoint Mullah Baradar As Head Of Political Office In Qatar, January 31, 2019.

[36] Bbc.com (UK), June 22, 2013.

[37] Huffpost.com (U.S.), September 22, 2013.

[38] Huffpost.com (U.S.), September 22, 2013.

[39] MEMRI JTTM report Photos: Taliban Delegation Led By Mullah Baradar Akhund Meets With Uzbek Officials In Tashkent, Visits Tomb Of Ninth Century Islamic Jurist Imam Bukhari, August 14, 2019.

[40] Voanews.com (U.S.), June 1, 2015.

[41] Alemaraenglish.com (Afghanistan), November 4, 2019; AlemarahVideo.org (Afghanistan), October 31, 2019.

[42] Nytimes.com (U.S.), October 31, 2018.

[43] Huffpost.com (U.S.), September 22, 2013.