In late January, the State Department informed Congress that Russia was not complying with the START III treaty, the only nuclear arms control treaty remaining in force between the two nations.

Russia, according to the State Department had refused to allow American inspectors into nuclear weapons facilities, an obligation under the treaty which will expire in 2026.

The State Department statement, as reported by The New York Times, read in part: "Russia's refusal to facilitate inspection activities prevents the United States from exercising important rights under the treaty and threatens the viability of U.S.-Russian nuclear arms control [...] Russia has also failed to comply with the New START treaty obligation to convene a session of the bilateral consultative commission in accordance with the treaty-mandated timeline."[1]

Dr. Alexei Arbatov, a member of the Russian Academy of Sciences, and the Head of the Center for International Security at the Institute of World Economy and International Relations (IMEMO) is worried. Arbatov, an arms control expert who was a member of the 1990 Soviet delegation that negotiated the original START treaty is concerned about the potentially impending end to the sixty years of strategic stability that were inaugurated after the world narrowly averted a nuclear holocaust during the Cuban Missile Crisis.

In an interview with the Russian daily Kommersant Arbatov is critical of the Russian leadership. In his opinion, if the agreement collapses, Russia will be plunged into a costly arms race where the U.S. can, at little cost, increase its quantity of nuclear warheads. Russia is also mistaken if it believes that it can use the agreement to pressure the U.S. into concessions on Ukraine.

Obviously, signing a new arms agreement is impossible in the toxic atmosphere prevailing today. Arbatov therefore urges Russia to reach a peace agreement or at least a long-term ceasefire based on Ukraine's neutral and non-nuclear status.

The interview with Arbatov follows below:[2]

Andrei Arbatov (Source: Aif.ru)

Q: "The fate of the START Treaty is now in question. The U.S. has accused Russia of violating the treaty for the first time since 2011, when it entered into force. Their claims are related to Moscow's refusal to set a date for a meeting of the advisory commission on the treaty and to agree to renew inspections of strategic facilities. Russia rejects the U.S. accusations, making counterclaims and insisting on changing Washington's policy on Ukraine. Do you think that the treaty could collapse prematurely?"

A: "Yes, the storm clouds are now gathering over the treaty and its future is in question. Past experience demonstrates that attempts to use such treaties as a tool of pressure on other issues do not make the other problems easier to solve but can undermine strategic agreements.

"After all, such treaties are by definition only reachable on the basis of an equal interest of the parties, and therefore it is unlikely that an additional 'bonus' will be received for them. A derailment of treaties (as in the case of the ABM Treaty, the Treaty on Conventional Armed Forces in Europe, the Intermediate-Range and Shorter-Range Missile Treaty (INF Treaty) and the Open Skies Treaty) is harmful to the security of both sides."

Q: "Could the U.S. denounce the START Treaty, as it did, for example, with the INF?"

A: "Provided the U.S. had a Republican administration (which some of us are dreaming about) and someone like Donald Trump were president, the Americans would easily withdraw from the START Treaty. However, the Democrats are in power in the U.S. now, they are more rational about strategic stability and nuclear arms control.

"It seems to me that under Joe Biden, the U.S. won't withdraw from START, unless something totally apocalyptic happens in Ukraine and pressure on him during the 2024 election campaign drives the president into a political corner."

Q: "So, in your opinion, even without commission meetings and inspections, the treaty can continue to operate until 2026?"

A: "Both the meetings of the bilateral consultative commission and, naturally, inspections on the ground are an integral part of the START Treaty. According to the treaty, the parties are entitled to carry out up to 18 inspections per year. The information gathered from such inspections is important both technically and symbolically. I very much hope that the parties will strive to resolve the issue of inspections and preserve the treaty."

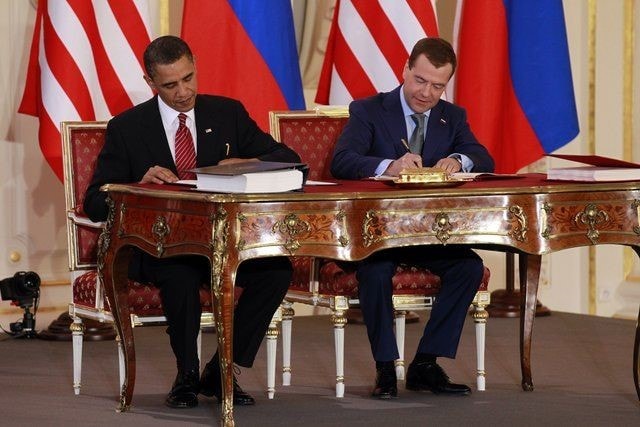

Presidents Barack Obama and Dmitry Medvedev sign the renewal of the START treaty. (Source:Telesur.net)

Q: "What if one of the parties, say, the U.S., announces withdrawal from the START Treaty, citing non-compliance on the part of Russia, as has already happened repeatedly with other arms control treaties? Or the situation just cannot get any worse than it is?"

A: "No, it would be much worse. Professional estimates demonstrate that the breakdown of the START Treaty would allow the U.S., if it so desires, to double or even triple the number of its strategic nuclear warheads in a few years with minimal expenses. After that, they can engage in the planned comprehensive renewal of nuclear forces with their hands untied.

"Strategic weapons are an extremely expensive and long-term issue. Strategic weapons have a life cycle of 30-40 years. They take 10 years to develop and test, then 10-15 years to deploy. They remain in service for another 20-30 years. Be that as it may, you have to plan ahead for decades.

"Meanwhile, the range of planning options diverges widely at the margins. And in the absence of treaties, each side..."

Q: "...will proceed from the worst-case scenario?"

"You are correct. It's conservative military planning. Each side will proceed from the worst-case scenario and invest to the hilt. An uncontrolled, unrestricted arms race will begin. Not only would it be extremely costly, but on top of everything else, the threat of war would increase. If we did not have such a treaty, the events unfolding now in Ukraine would very likely have brought us right to the brink of nuclear war."

Q: "Could you elaborate?"

A: "During the Cuban Missile Crisis, when there were no agreements and no arms restrictions, the Soviet Union feared a sudden U.S. nuclear attack. Back then, the Americans were much more powerful and had the ability to launch a disarming nuclear strike against the USSR. The U.S., in turn, feared a preemptive strike by the Soviet Union, precisely because the USSR could not then sustain a first strike and inflict a retaliatory [strike] and could only hope for a preemptive strike.

"A date was set for the U.S. air strike on Soviet missile bases in Cuba. And these missiles were already armed with nuclear warheads and their commanders were authorized to strike the U.S. in the event of an attack. Fortunately, the escalation was stopped in time. Had it lasted another 2-3 days, there would have been nuclear war. The entire east coast of the U.S. with its main cities and NATO member-states would have been wiped off the face of the earth, just as the Soviet Union, China and all its allies.

"Now, despite the heavy casualties and the completely unthinkable political and military situation, in which we find ourselves, on a strategic level no one is afraid of the first strike."

Q: "Nuclear war is the kind of thing people are seemingly afraid of now. The other day, the UN Secretary General António Guterres warned that 'the world is exposed to the greatest risk of nuclear war in decades, which could start accidentally or deliberately.' And in the autumn, U.S. President Joe Biden mentioned of the risk of 'nuclear Armageddon.'"

A: "Some say this, some say that, but not once has anyone said they feared a disarming strategic nuclear strike on part of the other side (which was the major fear in 1962). Thanks to the path we have taken in the past 60 years since the Cuban Missile Crisis and thanks to the dozen or so agreements that have been reached in this sphere, there is stability at the strategic level. Both sides are confident that a disarming strike by the 'counterpart' is impossible because a retaliatory strike is guaranteed.

"Therefore, when President Vladimir Putin announced late last February that the strategic deterrent was on special alert, the Americans said they would not put their forces on high alert and even cancelled a routine launch of the old 'Minuteman-3' missile, so as not to exacerbate the situation.

"The current concern is that conventional warfare in Ukraine could reach the point where nuclear arms are used for one reason or another, although Moscow has never directly and literally threatened to do so. This would trigger a NATO response, most likely a massive conventional missile strike against Russia, which would then retaliate more broadly against NATO, followed by the U.S. strike. They fear escalation in such a scenario."

Q: "So, nuclear deterrence works as a whole?"

A: "It works on the global level, but not in the combat theatre. The paradox of nuclear deterrence means that it is in theory designed to prevent unwanted actions by the other side via threatening them with catastrophic consequences, but it still does not provide a 100% guarantee that the enemy won't cross the red line. In turn, the opponent may not realize where this red line runs (especially as it is customary in Russia to maintain a veil of uncertainty to enhance the effect), or the opponent may think it's a bluff. Then, to prove that 'it is not a bluff,' one would have to actually deploy nuclear arms, causing the very catastrophic consequences that nuclear deterrence was intended to prevent."

Q: "And without treaties between Russia and the U.S., for example without the START Treaty or some other agreements, will this fragile ecosystem work?"

A: "This system won't work, because if an unrestrained nuclear or other arms race ensues, we will gradually lose a clear understanding of the enemy's capabilities, while the enemy will lose a clear understanding of our capabilities, and fears of a surprise disarming strike will return. In case of any crisis and direct military conflict there will be an incentive to overtake the enemy. After all, according to the President of Russia, what did the streets of St. Petersburg teach him?"

Q: "That one must strike first."

A: "Correct, if a fight is inevitable, you must be the first to strike. But exactly such a strike makes a fight inevitable, and applied to nuclear war ends in the destruction of both sides. After all, all the nuclear powers have repeatedly admitted that in a nuclear war, unlike in a street fight, there are no winners.

"The UN Secretary General António Guterres has called on the powers possessing nuclear arms to continue to disarm, or at the very least make a commitment not to be the first to use nuclear arms under any circumstances. Is there any chance that the powers possessing nuclear arms will heed his appeal, or have nuclear arms over the past year become more valuable to those who possess them and more attractive to those who do not?

"There is now virtually no chance of this proposal being accepted, and not just for political reasons. Of the current nine nuclear powers, only India and China have such a formal commitment (not to use nuclear arms first – Kommersant).

"For the most part, it's perceived globally as a political stance rather than an operational concept for the use of nuclear weapons in case of war. Readiness to deploy these arms in response to a nuclear attack is not in doubt. As for their first use, it is a very vague and doctrinally controversial issue.

"Most often, such a move is contemplated to repel aggression with conventional weapons when the existence of one's own state or allied countries to whom security guarantees have been extended is threatened.

"Nevertheless, in the distant future, such commitments could be a step towards a nuclear-free world, provided they will be based on practical control and limitation agreements, such as mutual reductions of the operational readiness of nuclear forces. But first, naturally, the threat of aggression with conventional arms must be removed, and for that to be achieved, mechanisms for peaceful conflict resolution must be established.

"Simply removing the concept of the disarming nuclear strike from current militarized and conflict-ridden international relations will not work, no matter how attractive the idea may sound.

"In light of the events of the last year, may God help us avoid a return to an unrestricted nuclear arms race, to an increased emphasis on a disarming strike strategy, and a new wave of nuclear proliferation beyond the 'nuclear nine' states."

Q: "Russia and the U.S. are now failing to reach an agreement on arms control, a sphere which has essentially become hostage to their conflict over Ukraine. There is a sense that during the Cold War, the situation was different, and the parties managed to reach some sort of solution in the sphere of strategic stability, despite the harsh confrontation in other areas. Why did it work then and why cannot it work now?"

A: "True, during the Cold War, following the 1962 Caribbean crisis, negotiations on practical (as opposed to propaganda-based) nuclear disarmament were generally successful and more or less uninterrupted. But at times there were many years between agreements, and not everything that was negotiated was ratified or fully implemented.

"However, there has never been such a thing as a year-long major military action in the center of Europe, in which one great power is fully involved and others are indirectly involved through the supply of arms and intelligence.

"Another thing should be kept in mind here. Back then, the contemporary leaders were participants in and direct eyewitnesses to the incredible suffering caused by the two world wars, remembered the horrors of Hiroshima, witnessed full-scale nuclear tests involving monstrous megatonnage. They had a certain reverent fear of nuclear arms as a precursor to the end of the world. Today's generation of politicians and strategists does not seem to feel any of that, they got used to nuclear arms and often treat them in a rather utilitarian manner, as a more or less effective means of politics, propaganda, and even actual conduct of warfare."

Q: "Given all that is happening today, how do you perceive the prospects for arms control?"

A: "It would be good to maintain at least what we have now. I'm convinced that strategic arms control is the linchpin, the supporting structure of international security.

"And since, thank God, we are not in a state of direct conflict with the U.S., and since we hope for a peaceful resolution of the Ukrainian crisis, this framework has to be maintained. To this end, we need to fully comply with the last of the current bilateral treaties in the field, the START Treaty, at least until its expiration in 2026.

"To start serious negotiations about what could replace the START Treaty is, in my view, unlikely to be successful until there is at least some progress towards peace in Ukraine, be it a long-term ceasefire or a real peace process."

Q: "In the most apocalyptic scenario, who would be more vulnerable, Russia or the U.S.?"

A: "Both countries will be at their most vulnerable, same as the entire Northern Hemisphere, while the Southern Hemisphere will return to Neanderthal era. Different experts provide different estimates of the likely losses, but they are all estimated to be tens of millions of lives lost.

"But they do not ask a question what to do, for example, with tens of millions of decomposing corpses, with billions of mutant rats spreading all kinds of infections. I won't dwell on the nightmares, but it is clear that the consequences of a nuclear war will be so terrible that few survivors will be able to remember and understand its cause."

Q: "So how do we get out of the current mess?"

A: "The first thing to do is to negotiate a ceasefire in Ukraine and then work towards a peaceful settlement. It is impossible to discuss the details at the moment, the situation 'on the ground' is constantly changing. But the main point of a ceasefire is to ensure Ukraine's neutral and non-nuclear status in exchange for recognition of its sovereignty and territorial integrity within the agreed borders.

"At the same time, Russia and the U.S. need to resume negotiations on strategic stability under the next strategic offensive arms treaty after 2026. Even without any disturbing effect caused by politics, this will be a very difficult undertaking. In addition to traditional nuclear 'triads,' restrictions on high-precision conventional long- and medium-range weapons, missile defense systems, tactical nuclear arms, and space systems will have to be negotiated. [It's important to] think about how one can incorporate China's rapidly growing nuclear capabilities and the forces of other nuclear powers into the regulations."

Q: "It looks like it's all going to be a big headache."

A: "Let's at least keep our heads and then we can deal with the headaches..."