Introduction

Will there be a mass uprising for democracy again in Tiananmen Square this year? Probably not. This is because Chinese President Xi Jinping has learned key lessons from his predecessors, Mao Zedong (1893-1976) and Deng Xiaoping (1904-1997). Both Mao and Deng had dared to open periods of free thought during their time in power. Both were surprised by the depths of discontent with the Chinese Communist Party (CCP) as expressed in "Big Character Posters [大字报 da zi bao]."

The crackdown that followed the democracy movement in Tiananmen Square on June 4, 1989 was but the latest fierce reaction to social unrest following a loosening of ideological control. Xi Jinping aims to cement CCP power over the population to prevent any expression of unhappiness with the current "harmonious socialist society." The Xi personality cult being developed in China is a strategy to maintain absolute power while allowing ordinary citizens to savor a certain measure of material wellbeing and a great deal of government-sponsored national pride.

How long will this strategy of repression endure and with what consequences? No one can predict. But one can learn a great deal by looking at what preceded the events in Tiananmen Square in 1989, and thereby glimpse why the CCP remains worried despite the relative quiet under Xi's reign. There remain signs of disbelief in the CCP in peripheral regions, such as Tibet, Xinjiang, and, especially in the last couple of years, Hong Kong. Therefore, the CCP will not allow any commemoration or discussion of the Beijing spring.

As June 4 approaches, many security forces will be called in to cordon off the square where students had erected a statue called "The Goddess of Democracy." No one will be allowed to speak about the estimated 10,000 wounded and killed. No photos of the lone man facing the row of tanks will be allowed on the internet – though intrepid netizens are already using an image of a young woman standing before tanks in Myanmar to call to mind the courage of the Chinese in 1989.All emojis of candles will be banned. The numbers 4, 6, 8, 9, when used in sequence, have already been erased from internet exchanges lest anyone call to mind the massacre in Tiananmen Square.

The foundations of this edifice, however, are shaky. A couple of weeks ago, an audio chat app called Clubhouse opened conversations among Chinese students around the world about forbidden subjects such as human rights violations in Xinjiang and the June 4 massacre. The app was shut down in China within days, but questions about the legitimacy of the regime endure. In Hong Kong, despite active measures to crack down on any dissent against the CCP and the arrest of prominent democracy advocates, the memory of June 4 will not be wiped out.

In the spring of 2020, the CCP used the COVID-19 pandemic to forbid all memorial gatherings. Nonetheless, thousands of citizens showed up with candles and masks in Victoria Park to remember the hopes shattered in 1989. More recently, just before the Lunar New Year, the Democracy Alliance of Hong Kong, put up a table in a flower market with a sign reading: "Re-think June 4! Let genuine righteousness prevail." Within one hour, the table was sealed off by police in the name of justice and the new security law.

Erased from history books, June 4 endures as a threatening date. As one Hong Kong artist shows, young people who were born after 1989 are taking on the struggle of their elders. Although their mouths are sealed, taped up against public commemoration, and the CCP looks threateningly over their shoulders, doubts about the autocracy of the current regime will not be silenced.[1]

What makes commemorations of 1989 so threatening is that they challenge the cult of Xi Jinping and loyalty to the CCP, which is supposed to be implanted in the mind of every Chinese man, woman, and child. This determination to enforce ideological uniformity was also a key part of the strategy developed by Mao Zedong from the 1940s through the Cultural Revolution of 1966-1976. Mao's policies depended upon a three-pronged scheme that started by imposing thought control, then allowing for some opening for criticism. The final stage is invariably a harsh reimposition of the CCP dogma by condemning as "enemies of the people" all those who dared to speak out during the window for dissent. Xi Jinping's current version of Maoism dwells on the first step of this strategy without risking any openness for criticism in the hope of avoiding the third stage, which required military action on June 4, 1989.

Mao Zedong: Rooting Out, As A "Poisonous Weed," Criticism Of The CCP

Before he became Chairman Mao and the "Red Sun that shines in the heart" of every Chinese person, Mao Zedong was a rebel within his own nascent Communist Party. The Cultural Revolution personality cult created a false history with Mao at its center. In fact, the Communist organization was started in 1921 upon the instigation of Lenin's Communist International, and is first adherents were prominent intellectuals from Peking University such as Chen Duxiu (1879-1942), Li Dazhao (1889-1927), and Zhang Shenfu (1893-1986). Among them, Mao was but a country bumpkin who was unfamiliar with Marxist theory and had never travelled to either Japan or the West.

From his earliest years as a communist, Mao Zedong promoted the potential of mass violence. Reporting on peasants who were murdering landlords in 1927, without any Marxist or communist ideology, Mao urged the party to follow the winds of change created by the masses. Instead of the Bolshevik model of the party leading the movement, Mao argued that communists should follow the people's will: "This upsurge is a colossal event. In a very short time China's central and southern and northern provinces will erupt like a mighty storm, like a hurricane, a force so swift and violent that no power, however great, will be able to hold it back."[2]

From 1927 onward, Mao remained a proponent of mass outbursts against authority. This aspect of his thought inspired not only the Cultural Revolution, but also the demonstrators of 1989. Gathering in Tiananmen Square, these young people were born after Mao's death in 1976. They saw no conflict between singing the communist anthem "Internationale" while clamoring for democracy. To their dismay, the activists of 1989 had not paid close enough attention to the third aspect of Maoist ideology, which requires crushing all signs of dissent.

Mao first showed his iron fist in 1942, when leftist intellectuals arrived in Yenan, Mao's stronghold in a cave hamlet behind the Japanese lines. At the opening of the May forum that year on "Art and Literature," Mao welcomed criticism of CCP methods in conducting the war of resistance to Japan. Assuming that these writers and artists were all supportive of communist ideology, he wanted to hear their views. Within days, however, Mao found that the critiques of the CCP's dictatorial methods had become intolerable and had to be silenced. The closed-open-shut strategy was now in full play. Some of those who dared to speak out were killed, others were sent to the countryside for brainwashing through "self-criticism" and hard labor.

In May 1957, the same strategy was applied when Mao had to cope with the ideological crisis of de-Stalinization in the USSR. Having been an admirer of Stalin from his first trip to Russia in December 1949, Mao was shocked by the secret news about atrocities following the dictator's death in March 1953. The Hungarian Uprising of 1956, which toppled statues of Stalin in Budapest, shook Mao even more deeply. Could this happen in China? To prevent the CCP's loss of power, Mao launched a movement to open a window of free thought upon the assumptions that ideological uniformity prevailed.

As in Yenan in 1942, Mao was not prepared for the depths of criticism against the CCP that were expressed through "Big Character Posters." Less than a month after promoting the open-minded sounding slogan "Let One Hundred Flowers Bloom, Let One Hundred Schools Contend," Mao started the anti-rightist campaign that destroyed 1.5 million lives.Every single person who dared to respond to Mao's call for criticism of the CCP's methods was declared a "poisonous weed" and "an enemy of the people." Each work unit also had additional quotas for finding, naming, and removing "rightists."

Brainwashing was again the order of the day as tens of thousands were sent to prison camps and to remote villages for hard labor. "Rightists" and their family members were required to write endless "self-criticisms" and make numerous promises of "self-reform." Deemed insufficiently sincere, these victims of Maoism were condemned to an even harsher fate than the rest of China during the Great Famine of 1958-80, which led to 34 million deaths, most of them in the countryside.

With the outburst of the Cultural Revolution in the summer of 1966, "Big Character Posters [大字报 da zi bao]" came into prominence again, this time directed against leaders of the CCP itself, something inconceivable in a Leninist-style organization. Mao launched his most dogmatic campaign against "revisionism," meaning anyone who did not totally believe his version of communism. Attacking, beating, and murdering high officials and prominent intellectuals became the norm from 1966 through 1969. Roving bands of Red Guards, fiercely loyal to Mao, fought violently amongst themselves. Their focus, however, was on victimizing well-known figures such as Chairman Liu Shaoqi (1898-1969), who was left to die alone, untreated, after being beaten severely and publicly humiliated. Deng Xiaoping's family, like that of Xi Jinping, suffered in the decade of violence that ended with Mao's death in September 1976.

Five months before Mao's death, and 13 years before June 4, 1989, another gathering in Tiananmen Square proved that Mao's strategy for brainwashing had not quite worked. On April 6, 1976, thousands came to commemorate the death of Premier Zhou Enlai (1898-1976) and to voice criticism of the extreme leftists, who were later labeled "The Gang of Four," including Mao's wife Jiang Qing. As in 1989, soldiers were called in to clear the square of all demonstrators and to tear down all signs of dissent. April 6, described by the numbers 4/6, or si liu in Chinese, which strongly echoes 6/4, or liu si, went down in Maoist history as a "counter-revolutionary uprising."

Deng Xiaoping: The Pragmatism Of Black And White Cats

One of the first acts after Deng Xiaoping came to power in 1977 was to change the verdict about the April 6 event and to call it "a patriotic" movement. Unable to foresee the depths of dissent, Deng Xiaoping launched broad reforms to privatize key sectors of the economy and open China's markets to an inflow of foreign investments and technological knowhow. In the 1980s, Deng Xiaoping strongly encouraged scholarly exchange with the West by sending and allowing thousands of Chinese students to travel abroad to gain scientific and technical skills useful for the building of a socialist economy. Assumed to be loyal to the CCP, these students learned far more than the limited skillset meant to prepare them for high positions upon return. They had imagined that Deng Xiaoping's era of openness would endure without the slamming shut that was characteristic of the Mao era.

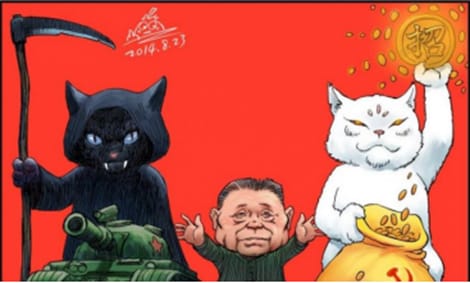

Deng's pragmatism before 1989 was encapsulated in a saying: "It doesn't matter whether the cat is black or white, as long as it catches mice, it is a good cat [不管黑貓白貓,捉到老鼠就是好貓]." Sanctioned by this earthy idiom, deeper conversations began, especially in universities and centers of scientific research, about the connection between economic development and freedom of thought. At Peking University, student leaders like Wang Dan (b.1969) and eminent scholars such as physicist Fang Lizhi (1936-2012) initiated "Democracy Salons" to argue for diminishing communist dogma in intellectual life and for genuine freedom of the press. On May 4, 1989, over a thousand TV and newspaper journalists signed a petition to this effect.

Calls for more freedom of thought, however, did not remain within the walls of the academy or within the pages of government-approved newspapers. Instead, the Beijing students were joined in Tiananmen Square by hundreds of thousands of other young people from all over China and by workers and businessmen as well. The huge central space dominated by the Mao Zedong mausoleum turned into a forum for debate about how to achieve a more democratic future. Deng Xiaoping came to dread the screaming that poured across the street through loudspeakers into the Party's secluded quarters. Once the students declared a hunger strike, their demands become more strident and evoked even greater sympathy from the citizens of Beijing. According to recently discovered documents, there was fierce disagreement within the CCP about the use of armed force against the students.Premier Zhao Ziyang argued for compromise and for meeting with protestors. Deng Xiaoping and his old army comrades, however, won the day. Tanks were called in and the massacre began on June 4, 1989.

Cartoon depiction of Deng Xiaoping's "Cat Theory" (source: Rebel Pepper via The Epoch Times)

Despite all the accomplishments of Deng's reforms, the pragmatism of black and white cats did not prevail. The closed-open-shut strategy of Mao was put into operation again. In 2016, Fan Di, a journalist for The Epoch Times published a scathing evaluation of Deng Xiaoping's "Cat Theory," accompanied by a cartoon showing the former leader of the communist party as the mastermind behind two nasty cats. A black cat, bearing a scythe and wearing a black hooded robe, is depicted as the Grim Reaper bringing death to Tiananmen Square while a white cat is a swindler shaking the tambourine of wealth monopolized by the princelings of the CCP.[3]

What Xi Jinping Learned From June 4, 1989

The current Chairman of the Communist Party and President of China Xi Jinping was 35 years old in 1989. He had no voice in the decision that led to the massacre of June 4. Nonetheless, since coming to power in 2012, and especially since abolishing all constitutional limitations to his term in office, Xi Jinping has been aiming to maintain only the first step of the Maoist strategy for total control of Chinese society. He is determined to avoid the risks of opening a window of free thought lest it lead to mass unrest and questions about the culpability of the CCP for many atrocities, including the use of tanks against unarmed students in 1989.

Drifting away from Deng Xiaoping's experiments with a more open society, Xi has been consciously modeling himself on the personality cult of Mao Zedong. In 2017, at the 19th Party National Congress, Xi Jinping launched his own slogan, "Four Confidences [四个自信 sige zixin]," which demand total obedience to the communist path, theory, system, and culture. This slogan was a conscious response to the "crisis of confidence [信仰危机 xinyang weiji]," which was seen as the legacy of Deng Xiaoping and especially of June 4.As a result of 1989, Marxist rhetoric no longer holds a central place in the hearts and minds of the Chinese people. Hence, Xi's ceaseless efforts to enforce discipline and ideological unification.

In the past two years, "Xi Jinping Thought" has become a required subject of political study throughout China. The goal of this campaign, as in the era of Mao Zedong, is to create unanimity of belief that will prevent outbursts such as those that occurred in Beijing in the spring of 1989. The publication of Xi's multi-volume works has provided the foundation for a new personality cult that echoes the dogmatism of the Cultural Revolution.

Even if nothing happens in Tiananmen Square on June 4, 2021, Xi Jinping's regime will not rest easily. Its propaganda assumes that the CCP is synonymous with China and that it deserves both political and cultural loyalty. This line, however, no longer rings true. A mind, once opened, cannot be totally slammed shut. Voices can be silenced and the Clubhouse app can be shut down, but gnawing doubts about the legitimacy of the regime that practices Maoist brainwashing in the 21st century deepen with the passage of time.

The memory of 1989 has not been successfully erased. It remains a huge question in China and in the consciousness of the global community. Despite Xi Jinping's rhetoric of a harmonious shared human destiny, the facade of the CCP is wearing thin. Perry Link, foremost scholar of the Beijing Spring in the West, wrote the following call to conscience on June 4, 2019, which was the 30th anniversary of the events: "We remember June Fourth because the worst of China is there – but the best of China is there, too. We remember June Fourth because it was a massacre – not just a crackdown, or an 'incident,' an event, a shijian, a fengbo; not a counterrevolutionary riot, not a faint memory, and not, as a child in China might think today, a blank. It was a massacre. We remember June Fourth because... It is the only case in which a nation invaded itself. We remember June Fourth because Xi Jinping's fat smile is a mask... We remember June Fourth in order to support others who remember. We remember June Fourth because remembering it makes us better people."[4]

Masks are falling even if a deafening silence will be imposed upon China in June 2021. No amount of propaganda can fully erase the longing for freedom of thought which still flourishes in Hong Kong, in Beijing and beyond.

*Vera Schwarcz is a Special Advisor to MEMRI. She is Emerita Professor at Wesleyan University and a Senior Researcher at the Hebrew University, Jerusalem.

[1] Jun Mai, "Thirty years on from Tiananmen Square Beijing still thinks it got it right," South China Morning Post, May 20, 2019.

[2] Mao Zedong, "Report on an Investigation of the Peasant Movement in Hunan" (March 1927), Selected Works, Vol. I, pp. 23-24.

[3] Fan Di, "Reflecting on Deng Xiaoping's 'Cat Theory' of Economic Reform," The Epoch Times, October 18, 2016.

[4] Perry Link, "Why We Remember June Fourth," China File, May 28, 2019.