On December 15, 2019, Pakistani security analyst Muhammad Amir Rana penned an article about his recent visit to Xinjiang, the restive region of China, where the Chinese authorities have rounded up a large number of the Turkic Uyghur Muslims and lodged them in deradicalization camps. China admits to having arrested 13,000 Muslims in Xinjiang, whom it describes as "terrorists."[1]

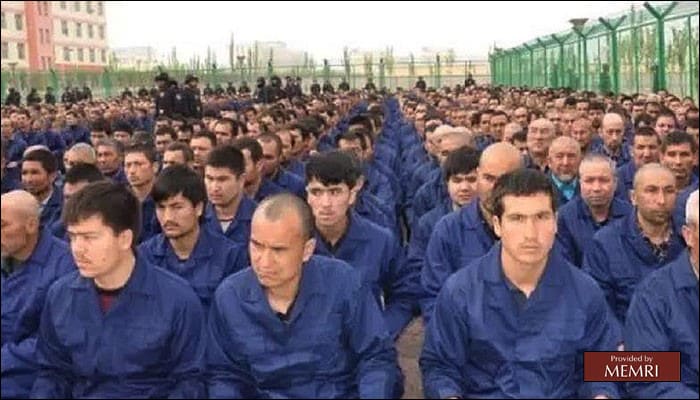

In October 2019, Louis Charbonneau, the UN director at Human Rights Watch, wrote: "There are credible estimates of at least one million Turkic Muslims being indefinitely detained in 'political education' camps. China's harsh repression also involves widespread surveillance and the destruction of Turkic Muslim cultural and religious heritage across Xinjiang."[2]

Uighur Muslims in a detention camp in Xinjiang

Ambassador Karen Pierce, the UK's Permanent Representative to the UN, read a statement on behalf of 23 countries at the UN's Third Committee session on the Committee for the Elimination of Racial Discrimination, saying: "credible reports of mass detention; efforts to restrict cultural and religious practices; mass surveillance disproportionately targeting ethnic Uighurs; and other human rights violations and abuses in the Xinjiang."[3]

In view of international criticism, China has permitted journalists to visit Xinjiang. But these visits are coordinated and monitored by the Chinese authorities, thereby preventing objective ground reports from Xinjiang. Muhammad Amir Rana, who recently visited Xinjiang, writes in an article about his visit that China's policy of forced deradicalization is in line with the rise of "exclusionism, supremacism, and hyper-nationalism" in certain parts of the world.

Following are excerpts from his article:[4]

"The Chinese Definition Of Extremism Is Complicated As It Hardly Differentiates Between Religious, Ethnic, Linguistic, And Cultural Grievances"

"Tensions China and the U.S. have escalated after the House of Representatives' Uighur Human Rights Policy Act, 2019. The move is of a piece with the allegations of many international media and human rights organizations that China is persecuting the Uighur community and violating their rights — allegations that Beijing has denied. Calling the U.S. action a political move aimed at damaging its international image, China says it is running a deradicalization programme to mainstream its communities.

"The Chinese claim has not been verified by independent sources and mystery shrouds its deradicalization or re-education program. China needs to demonstrate to the international community that it has inserted human rights safeguards in its deradicalization measures.

"On their part, the Chinese say that they are countering violent extremism (CVE) with a strategy that has been designed after a careful examination of CVE approaches in the West and in the Muslim world which also employ deradicalization programs. The Chinese view has been challenged by those who point out that standard global CVE practices are different from those espoused by China, and that global CVE practices are mostly conceived when countering terrorism perspectives.

"Secondly, the Chinese definition of extremism is complicated as it hardly differentiates between religious, ethnic, linguistic, and cultural grievances. Nor does this definition describe separately the different sociopolitical manifestations of extremism, of both the violent and nonviolent variety. The Chinese deradicalization program is also a massive exercise in the sociocultural engineering of its minority communities."

"Uighur Muslims Complain They Are Paying A Huge Cost For This 'Harmonization Process', Which Is Causing Them To Lose Their Religious, Ethnic, And Cultural Identities"

"China's communist party states that 'harmony' is the core driver of state policies as exemplified in its Belt and Road Initiative [BRI] vision. The idea of 'harmony' or 'harmonization' could have been conceived as a substitute for the regular democratic process, but has, instead, become a driver of legislative and administrative reform, including 're-education' strategies.

"However, China is still striving to generate a framework for 'harmonizing' its ethnic and religious communities. Chinese scholars believe that adopting a muscular approach to 'harmonizing' minority communities is the fastest way to make the autonomous and administrative regions trouble-free.

"Uighur Muslims complain they are paying a huge cost for this 'harmonization process', which is causing them to lose their religious, ethnic, and cultural identities. They find only a few voices being raised in their support in the Muslim world. The Muslim leadership, which is greatly concerned by Islamophobia, has apparently shut its eyes to the Uighur issue. Their silence is rewarded with Chinese economic assistance and diplomatic support on international forums.

"Though Chinese authorities believe they will be able to achieve their envisioned sociocultural transformation, they are nervous about their global image. This year, China opened one 're-education' center for international visitors in Kashgar, inviting diplomats, academics and journalists to visit it, in an attempt to counter international perceptions. But so far, such attempts have not impressed foreign visitors.

"While the center seemed different from the images that appeared in the international media, the well-articulated responses of the trainees there created doubts in the minds of visitors. Secondly, Chinese authorities do not provide the exact number of deradicalization centers, but according to the international media, at least 85 such centers have been set up in parts of the country, mainly in the Xinjiang region."

"Chinese Historians And Scholars Are Making Efforts To Convey To Their Muslim Populations That They Have Been A Part Of The Chinese Civilization For Thousands Of Years"

"One component of China's counter-extremism framework is to challenge radical narratives, which is resulting in attempts to forge a new ethnic and cultural identity for Xinjiang's Uighur community. They are reinterpreting the history of Xinjiang and Muslims in China.

"According to some books and booklets, provided by the authorities to visitors, Chinese historians and scholars are making efforts to convey to their Muslim populations that they have been a part of the Chinese civilization for thousands of years. Their emphasis on cultural integration is part of a multi-layered strategy.

"A booklet, titled 'Historical Matters Concerning Xinjiang' and published by the State Council Information Office in 2019, rejects the idea that Xinjiang has ever been referred to as 'East Turkestan'; saying that there has never been any state with this name.

"According to the booklet provided by the state authorities, at the turn of the 20th century, terms such as 'pan-Turkism' and 'pan-Islamism' 'made inroads in Xinjiang' and 'separatists in and outside China politicized the geographical concept and manipulated its meaning, inciting all ethnic (Muslim) groups speaking Turkic languages ... to join in creating the theocratic state of East Turkestan.'"

"The Authorities Are Attempting To Introduce A Local, Chinese Version Of Islam On The Pattern Of Its Previous Exercise Of Nurturing Socialism With Chinese Characteristics"

"Chinese language courses are compulsory for Muslims because of communication barriers with Uighur and other Muslim communities, according to the Chinese authorities. An unusual aspect of this exercise is that the authorities are attempting to introduce a local, Chinese version of Islam on the pattern of its previous exercise of nurturing socialism with Chinese characteristics. For this purpose, Beijing has established Islamic learning centers to prepare imams, or prayer leaders, who can preach the 'Chinese version' of Islam.

"The curriculum of Islamic centers includes Chinese language, history, constitution, law, and culture apart from religious knowledge. These centers are not allowed to collaborate with other Islamic institutions in Muslim countries.

"At a center in Urumqi, the principal argued that religious institutions in Muslim countries focus on religious education and are divided along sectarian lines, but that the centers in China had adopted the values of socialism and developed compatibility between religion, patriotism and social cohesion. The principal told a group of international writers, including this writer, that 'Chinese Islam has no space for the evils like extremism and separatism.'

"The Chinese authorities complain that Uighur Muslims are not law-abiding citizens. A booklet – titled 'Vocational Education and Training in Xinjiang,' published by the State Council Information Office – provides insights into the Chinese view of the issue when it claims that extremist forces act in accordance with 'fabricated religious law' and 'domestic discipline', and defy the country's constitution and laws.

"It is interesting that at a time when exclusionism, supremacism, and hyper-nationalism tendencies are globally on the rise, China has decided to launch its own version of 'harmonizing' society. This thinking might appear to negate the global trends but in essence, its objectives are similar, and it has little space for accepting diversity."