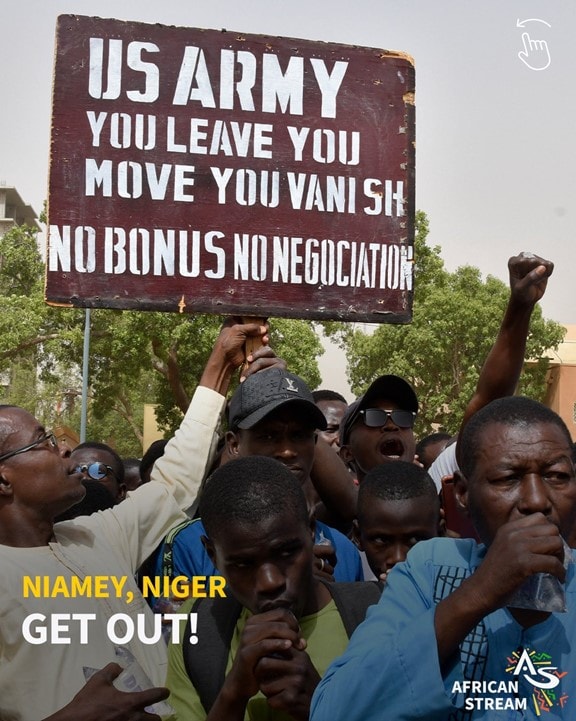

Six months after French soldiers were expelled from Niger, it is now the turn of American troops to be invited to leave the country. The Americans had been in force in Niger for less than a decade and had spent well over $100 million in building a counterterrorism base near the northern city of Agadez. Now the military junta ruling the country since July 2023 not only asked the Americans to leave, they seem to have done so directly.[1] According to Le Monde, Nigerien Prime Minister Ali Lamine Zeine had told the State Department's number two official, Kurt Campbell, that "the American contingent was no longer welcome."

Le Monde lamented that the Sahel, a huge swathe of poor but mineral rich countries stretching from the Atlantic Ocean to the Red Sea, "has become the playground of foreign powers, first and foremost Russia."[2] That is in fact not quite true as Niger has not only reached out to Russia, but also to China, Iran, and Turkey. And, of course, the Sahel has been the "playground of foreign powers" for decades, first and foremost France, but also the United States and, some years ago, Qaddafi's Libya and even Saudi Arabia. On my sole visit to Niger a decade ago, the country's interior minister told me how Nigeriens had been Muslims for a thousand years, "but then they go to Saudi Arabia and are indoctrinated that we have been doing it all wrong all this time."

There is no doubt that the Russians have gained in influence in Africa, step by step, at the expense of France and the United States, over the past decade.[3] It was in 2015 that Russia's direct intervention in Syria helped a weakening Assad regime hold onto power. The Russians then followed up by intervening in Libya's Civil War helping the forces of Libyan strongman Khalifa Haftar. Then in 2017, Russia – spearheaded by the Wagner PMC – appeared in both Sudan and in the Central African Republic. While Wagner (or its successor) today is closely identified with the forces of Sudanese warlord Muhammad Hamdan Dagalo "Hemedti," Russian military contractors were invited into Sudan by the previous Bashir regime and Russia has been friendly with both sides of Sudan's current civil war. In the Central African Republic, one of the world's most miserable countries, the Russians have been able to strengthen the regime of President Touadéra. The country's long existing problems, festering long before Wagner, continue.[4] Wagner was essentially offering cut-price security enhancement for embattled regimes, something that some African countries had gotten in the past from French, English, South African or Cuban mercenaries.

Military coups in Mali (2021), Guinea (2021),and Burkina Faso (2022) have all brought into power regimes that are – at best – skeptical if not hostile to France, but to date only Mali has Russian troops on the ground. After being expelled from Niger, the French (and Americans) fear that the same will happen in Chad, a historic bulwark of French influence.[5] President Mahamat Deby visited Moscow in January 2024 but he recently sought to reassure the French in an interview with RFI/France24 when asked if he was considering replacing a French alliance with a Russian one. Deby responded, "Chad is an independent, free, and sovereign country. We are not like a slave who wants to change masters. We intend to work with all the nations of the world, all the nations that respect us."[6] This nakedly transactional view of international affairs is widely shared in much of Africa.

Think pieces lamenting the fall of Western influence in this part of Africa and the noxious influence of Russia have been a bit of a cottage industry, especially since the beginning of the Ukraine War.[7] Many of them focus on lack of Russian respect for human rights and Russian disinformation, issues where the Russians are notorious but hardly unique.[8] Both French and UN troops have faced charges of human rights abuses in many of the same countries. Propaganda is beamed into the continent by a variety of state and non-state actors. And Russian plundering of natural resources follows similar plundering carried out by neo-colonial powers for decades.

But perhaps the biggest danger for the West in Africa though is not Russia, or Russia alone, but rather a disastrous global byproduct of the Ukraine War, the bringing together of Russia, China, and associated powers in a tight-knit alliance not seen before. It is hard to recall that, not so long ago, the Americans regarded Russia as helpful on Iran and North Korea. Today both of those countries are key partners in the Russian war machine. In Mali, Russia provides security while China provides much needed investments in lithium mining.[9] African countries needing inexpensive, deadly drones can turn to Russian ally Iran. Construction projects can be outsourced to the Chinese or Turkey for much more reasonable costs than what can be provided by the West.

Russia, China, Iran, and North Korea had ties before the Ukraine War but they are much closer today. What began as a defensive marriage of convenience in response to American sanctions and Russia slowly losing in 2022 risks becoming something much more significant the longer this disparate group bands together. It is too early to tell whether an alliance created initially for sanctions busting can actually project joint political and security power in Africa as a challenge to the West. Russia alone can only offer some limited benefits to these new African military regimes. Russia and friends can offer more. For regimes that do not rely on trade with the West, regimes that sell one easily fungible product (oil or gold or uranium, for example), their new friends from the East can provide them what they want more cheaply, with less hassle and strings attached, and with far less preachiness and arrogance. Russia, Iran, and China may be gaining new allies in the Sahel, but they already have some old allies in Algeria and South Africa.

The West's saving grace in this new stage of the struggle for Africa is the same reality that got them in trouble in the first place: the cynical, transactional nature of diplomatic relations for many of these authoritarian regimes. They were, and remain, volatile regimes that can reverse course as circumstances shift.[10] The bazaar is always ready for bargaining and the "playground" is open for any player willing and ruthless enough to play the game.

*Alberto M. Fernandez is Vice President of MEMRI.

[1] Twitter.com/african_stream/status/1782472509448683779, April 22, 2024.

[2] Lemonde.fr/idees/article/2024/04/22/desastreuse-retraite-occidentale-au-sahel_6229179_3232.html, April 22, 2024.

[3] Csis.org/analysis/russias-corporate-soldiers-global-expansion-russias-private-military-companies, July 21, 2021.

[4] Capedassociation.org/sites/default/files/2019-12/Revue%20Dialectique%20des%20Intelligences%20n06-2019-Semestre1.pdf, 2019.

[5] Twitter.com/TchadOne/status/1781251256289214664, April 19, 2024.

[6] Rfi.fr/en/africa/20240420-chad-is-not-a-slave-who-wants-to-change-masters-says-president?utm_medium=social&utm_campaign=x&utm_source=user&utm_slink=rfi.my%2FAXB9, April 20, 2024.

[7] Cfr.org/backgrounder/russias-growing-footprint-africa, December 28, 2023.

[8] Africacenter.org/fr/spotlight/cartographie-de-la-vague-de-desinformation-en-afrique, April 1, 2024.

[9] Afr.com/companies/mining/perth-lithium-player-strikes-250m-deal-with-china-s-ganfeng-20210616-p581e5, June 16, 2021.

[10] See MEMRI Daily Brief No. 512, The Great Game In The Sahel, August 10, 2023.